“I was going to make a tackle, and I just blacked out,” he said.

This was Bryant’s most recent concussion, and he says he has had about three or four since he started college. Bryant is not the only college athlete who has had to deal with concussions. According to concussiontreatment.com, the Centers for Disease Control estimates that 1.6 million to 3.8 million concussions occur each year, and five to 10 percent of athletes will become concussed in any given sport season.

Head Athletic Trainer Ned Shannon oversees the health care that student athletes receive at the University of Indianapolis. According to Shannon, a concussion can be defined as a transient impairment of neurological function. In other words, it is a brain injury. Shannon said that while there are many definitions for a concussion, the one aspect that each definition agrees on is that the injury is usually not permanent and is caused by blunt force trauma.

According to Shannon, a concussion can result in a loss of consciousness, but that is rare in sports.

“You have this protective equipment,” Shannon said. “You’ve got things like rules in the game that prevent injury. Then you’ve got things like good coaching that teach you not to hit your head on something. So injuries that don’t result in loss of consciousness are typically what are seen in athletics.”

According to Shannon, every NCAA college is required to have a concussion protocol. Shannon said that at UIndy, if an athlete is injured during a game or practice, he or she is pulled out of the situation.

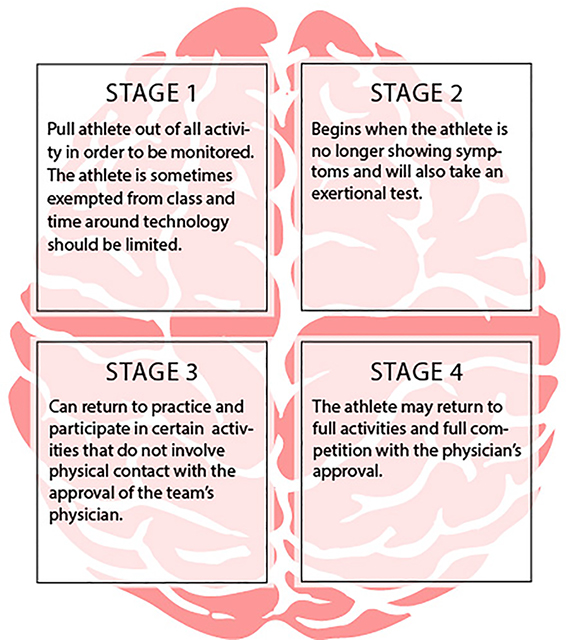

A sideline evaluation is done that will give the trainer an idea of how severe the concussion may be. After it is determined that the athlete does have symptoms of a concussion, the four-stage concussion protocol begins.

According to Shannon, the first stage involves pulling the athlete out of all activity in order to monitor him or her while he or she is symptomatic. Symptoms of a concussion include problems with memory, confusion, drowsiness, dizziness, double or blurred vision, headaches, nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to noise or light, balance problems and slowed reaction to stimuli, according to healthline.com.

Once an athlete’s symptoms are documented, he or she must take a neurocognitive test called Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing. When student athletes arrive at UIndy, before they begin training, Shannon said they all are required to take ImPACT. The test asks students questions such as their name and the sport they play, as well as symptom questions such as whether or not the student has a headache.

Shannon said that once the student is concussed, he or she will take a post-ImPACT test to monitor his or her symptoms and improvement. The test usually is taken within a day or so after the concussion occurs, Shannon said. The concussed student also will visit with the team physician from the Methodist Sports Medicine Center. The team physician will conduct his or her own evaluation with the student as well, Shannon said.

During stage one, Shannon said that the concussed athlete may not go to class and will be asked to limit his or her texting, time on the computer and time spent playing video games, as these activities require the brain to work while it is injured. Shannon said a lot of athletes ask how long it will take for them to be well enough to return to practice or competition, but Shannon said there is no set timeline.

“Every concussion is different,” he said. “We’ve had some athletes come back [in] as few days as seven or eight days, and we’ve had some athletes be out [for] months from typically the same level of concussion. It just depends on how the person heals.”

Stage two begins when the athlete is no longer showing symptoms. He or she can return to class, do homework, text and get back to his or her regular routine. From the athletic perspective, the athlete will take an exertion test. Shannon said this means he or she either will run on the track, get on a treadmill or ride the stationary bicycle for about 10 minutes to increase blood pressure, heart rate and breathing rate. Shannon said this test is necessary because it is possible that symptoms will come back during this process. If the symptoms of a concussion do come back during exercise, Shannon said that simply means the brain is not completely healed yet. Once the athlete is able to take the test without the symptoms returning, he or she can move on to stage three.

During stage three, with the team physician’s approval, the athlete can go back to some level of practice and participate in portions where they will not be hit. Shannon said the student will not be required to wear extra protective gear or be limited in any way at this stage.

Stage four is the final stage, when the athlete can go back to full activity and full competition, with the physician’s approval.

Shannon said that while trainers and coaches watch out for injuries, it is also the responsibility of the athlete to report if something is wrong. According to Shannon, all athletes are required to sign a document stating that they will report to someone in authority if they think they have sustained a concussion because the health risks can be major.

“One of the biggest concerns of parents, athletic trainers and sports physicians is athletes who underreport, meaning they don’t say anything about their concussion, [and] they continue to participate and they get hit again. … Now that seemingly mild concussion, if there is such a thing, becomes a much more significant problem,” Shannon said. “You might end up with more significant symptoms, longer time away from sports, hospitalization—so there’s some very, very serious effects if you withhold that information, and you [get] injure[d] again.”

Shannon said that an athlete will go through the stages even if the injury that caused the concussion did not happen during practice or a competition. For example, if an athlete is concussed by slipping on the ice while walking across campus, he or she still has to go through the four stages. There is not a quota of concussions a student must not hit in order to play sports, but Shannon said that some athletes choose not to participate after receiving a frequent number of concussions.

Bryant said he had to go through all four of the stages after receiving his concussion. And while he said it was a lot of work to get back to playing football, he agrees with the process.

“I think they go about it pretty well,” he said. “And they don’t rush you back too fast. … Some coaches [outside of UIndy] ignore the fact that you have a concussion, and they just let you stay in the game.”

Shannon said that the Greyhound coaches are diligent about following the protocol and put athletes’ health above the game.

“There’s very little pressure, if any at all, from coaches to athletes to return to play faster. … Our coaches do an outstanding job at participating with the return to play of the athletes safely,” he said.

Bryant said he believes athletes should follow this example and take care of themselves by letting someone know if they are concussed.

“I would just tell them [athletes] to let somebody know,” Bryant said. “Don’t be afraid to make people aware of your situation because you want to stay in the game. You’re not helping yourself, or you’re not helping your team. It’s not that big of a deal to stay out of a game [rather] than risk your health like that.”

ORIGINAL ARTICLE:

http://reflector.uindy.edu/2015/12/16/concussion-protocol-monitors-uindy-athletes/