Article reposted from Pittsburgh Post Gazette

Author: SEAN D. HAMILL

Those who have viewed the 12 hours of video surveillance that show the slow and painful death of Tim Piazza that resulted from what happened the night of Feb. 2 and Feb. 3, 2017, say it is horrifying to watch.

As the heavily intoxicated 19-year-old sophomore Penn State engineering major stumbles, crawls, and falls down repeatedly, losing consciousness multiple times, it is the indifference of the more than two dozen of his Beta Theta Pi fraternity brothers that is hard to understand.

But there is one small moment, just after 5 a.m. the morning after Mr. Piazza began drinking, when fate cost him at least one chance at surviving.

He had stumbled into a side room off of the house’s great room, where during the pledge ceremony the night before he had joined the fraternity. There, lying on the side room floor, he was, for a time, in sight of a surveillance camera and the doorway into the great room.

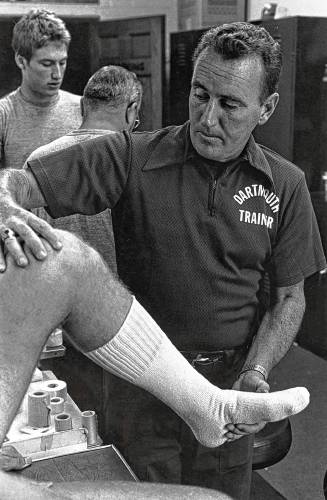

Mr. Bream was not only the live-in adviser, he was then and now one of the most prominent members of the Penn State athletic staff, head athletic trainer for all university sports and head football trainer for the Nittany Lions. A Penn State and Beta alum himself, Mr. Bream decided to “give back” to his alma mater by taking the job in 2012 in the wake of the Jerry Sandusky scandal after being head trainer for the Chicago Bears for 15 years.

“It is not hyperbole to say that when Tim Bream was sleeping in his room while this incident unfolded, he represented one of the most capable people in the world to respond to the trauma of a young man since he deals with trauma daily,” his attorney later wrote in a motion that attempted to prevent Mr. Bream from testifying as a witness in the preliminary hearing to the criminal case of the fraternity brothers charged in Mr. Piazza’s death. Mr. Bream is not charged in the criminal case, though 28 fraternity members are.

Even though several fraternity members discussed it, no one went to Mr. Bream’s room on the second floor at the far end of house to wake him up to check on Mr. Piazza in the seven hours before Mr. Bream left for work that morning. And because Mr. Piazza had moved out of sight of the doorway, Mr. Bream never saw him in distress that morning as he left the house.

In testimony when he did appear at the preliminary hearing, Mr. Bream said while he knew the fraternity had applied for an alcohol permit for the pledge party, he never learned if it was granted and he knew nothing about what went on at the party after he went to his room after 9 p.m., where he stayed until leaving just after 5 a.m. the next morning.

But attorneys representing some of the fraternity brothers charged in the criminal case, as well as civil attorneys for the Piazza family and a Beta alum who paid to renovate the fraternity house, believe Mr. Bream cannot escape his share of responsibility for what happened that night – even though he has not been charged in the criminal case.

“Bream was the captain of the ship,” said Leonard Ambrose, attorney for one of the defendants, Joe Sala, 19. “When you have a captain on the ship and it runs into the dock when the captain was sleeping, the person in charge of the ship can’t just walk away from this by saying, ‘I was sleeping.’”

It was Mr. Ambrose who called Mr. Bream to testify as a witness in the preliminary hearing.

In an email, Mr. Bream declined to comment, writing: “At the advice of my attorney I will not comment or be interviewed.”

Michael Leahey, an attorney representing the housing corporation board that owns the Beta house, which includes Mr. Bream as a board member, said Mr. Bream would never have done anything to put students in harm’s way.

“Tim has devoted his entire life to helping young men,” he said.

Though Penn State, through spokeswoman Lisa Powers, answered some questions, it refused to answer whether Mr. Bream bore any responsibility for what happened the night Mr. Piazza was hazed and fatally injured because it did not “want to speculate on the issues.”

Stacy Parks Miller, who was the Centre County district attorney when the charges were filed last year, told reporters last year that she did not charge Mr. Bream because he was “not a participant in the crime.”

At a press conference after one of the preliminary hearing sessions in August, she dismissed defense attorneys’ attempts to try to put responsibility on Mr. Bream as nothing more than a “red herring.”

“What they want to say is they believe Mr. Bream, because he’s 58-years-old, somehow makes their client not guilty because he was living in the house,” she said, getting his age wrong.

But many of the attorneys and families involved in the criminal and civil lawsuits still have many questions. They are as much about what Mr. Bream did or didn’t do the night Mr. Piazza was fatally injured before dying on Feb. 4, 2017, as they are about what he could have done before the night of drinking even began.

And many have wondered why a 56-year-old man was living in a fraternity house that was home to 40 college students and known for its hard partying.

Part of the answer lies in understanding Mr. Bream’s background and how loyalty guided his decisions, first, to take the job at Penn State, and, second, to move into the Beta house.

He was born Henry Trostle Bream III in Gettysburg – he still signs formal documents “Henry T. Bream III” – the son of a prominent Gettysburg sports family that gave him the nickname Tim.

He was named after his grandfather and an uncle, who also went by the nickname Tim, who died in 1939 when he was just 9 years old, long before Mr. Bream was born.

His grandfather was Henry T. “Hen” Bream, a legendary longtime coach and athletic director at Gettysburg College, which named its gymnasium after him when he retired. When he died in 1990, it was front page news in The Gettysburg Times.

Tim Bream’s father, Jack Bream, followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a successful coach and administrator at Gettysburg College. It was Jack Bream’s struggle with alcohol that led Tim Bream to decide he would never drink any alcohol, Tim Bream said in his testimony this past August. Jack Bream declined to comment for this story when reached by the Post-Gazette.

Led into sports by his father and grandfather – both of whom were successful athletes themselves at both Gettysburg High School and Gettysburg College –Tim Bream followed a slightly different path in sports.

“I was a mediocre athlete,” Tim Bream told The Gettysburg Times in 1982 in a profile on his fledgling athletic training career as a senior at Penn State working the sidelines of Nittany Lion football games. “Being a trainer is the best way for me to keep in touch with sports.”

He bucked his family tradition and went to Penn State, where he joined the Beta Theta Pi fraternity. But going to Penn State probably wasn’t as strange a move to his family as it might have seemed, given his father’s and grandfather’s history.

As with any story involving Penn State over the last half century, there is a Joe Paterno link in the story.

As detailed in multiple stories in The Gettysburg Times over several decades, Tim Bream’s grandfather was a close friend of Mr. Paterno’s, and the two longtime football coaches visited each other regularly.

When Tim Bream graduated from Penn State in 1983, he spent the next decade moving up through the ranks at four different universities, including at Syracuse, where he met his future wife, Lisa.

They married in 1986 and raised two daughters together, eventually moving to Chicago where Mr. Bream in 1993 landed a job as assistant athletic trainer with the Chicago Bears. In 1997 he became head athletic trainer, and life seemed to be good for the Bream family.

Then the Jerry Sandusky child abuse scandal broke at Penn State in November 2011. A month later the university’s new athletic director, Dave Joyner, called Mr. Bream to offer him the job to be the new head athletic trainer.

“To be honest, if any place other than Penn State had called, I wouldn’t have even considered it,” Mr. Bream later wrote in 2015 for the Training & Conditioning website about his decision.

He quickly accepted the job and moved his family to State College, buying a new home on the edge of town, in the spring of 2012.

But even before Tim Piazza’s death, the move would prove to be fraught with struggles for Mr. Bream.

After just one season as the football team’s head trainer, he was a focus of a Sports Illustrated article in May 2013 that claimed he was making questionable decisions with players, including giving players medications that he was unqualified to distribute.

Penn State investigated the claims even before the story was published, found them baseless, and Mr. Bream kept his job.

Not long after that, though, Mr. Bream separated from his wife of 27 years and filed for divorce in September 2013 because the marriage was “irretrievably broken,” his attorney wrote in the divorce petition.

The Breams were “unable to agree on an equitable distribution,” according to the petition, and they needed more than two years to divide their assets. Mr. Bream agreed to give his wife the home they had purchased together, nearly half of their savings, and pay his ex-wife about 40 percent of his annual $138,000 Penn State pay until 2020. Ms. Bream declined to comment when reached by the Post-Gazette.

The final order would not be signed by the divorce judge until May 2016.

It is not clear if Mr. Bream had been looking for a place to stay before he moved into the second floor room in the Beta house on Aug. 15, 2016. During his divorce he listed his mailing address as being at the Lasch Building, where the Nittany Lions athletic staff works.

But in a brief filed by his former attorney, Matthew D’Annunzio, when Mr. Bream was trying to avoid testifying at the preliminary hearing, Mr. D’Annunzio wrote that Mr. Bream “agreed to the repeated requests from his friends on the board of the Housing Corp. to undertake the role of adviser.”

It is because Mr. Bream was the hand-picked representative of the housing corporation – which had banned alcohol from the Beta house – that attorneys believe Mr. Bream bears some responsibility. That is despite Mr. Bream saying in testimony that his job was not to check on parties to make sure alcohol was not present.

“That’s not my role,” he said at the Aug. 30 hearing. “My role [as house adviser] is more of guidance, a person of guidance. It wasn’t an overlord, an overseer. I wasn’t in charge of discipline at all.”

But an attorney representing the Piazza family said the terms of any agreement with the housing corporation that allowed Mr. Bream to live in the house have not yet been made public.

“He didn’t just walk in there on a handshake. There has to be some memorandum of understanding,” said Tom Kline, the attorney for the family, which has not yet filed any lawsuit in the death of their son. They have two years from his death to file a lawsuit.

Even if he did not know if it was granted, Mr. Bream’s testimony that he knew that the fraternity had applied for an alcohol permit to the Interfraternity Council “is a very important point” since the housing corporation had banned alcohol in the house, said Mr. Ambrose, the attorney for a fraternity member.

“If anybody should have put a stop to [the fraternity party] it was Tim Bream,” he said. “But he allowed it to go on. And [for the fraternity brothers] that was tacit approval.”

Mr. Bream stunned the more than two dozen defense attorneys when he answered questions as a witness at the preliminary hearing. Because he was in the house when Mr. Piazza was hazed and then injured, they thought he would cite his 5th Amendment right against self incrimination and not answer many of the questions about his role in the house or what he knew about the party that night.

Mr. Ambrose said he believes that the adviser role, as Mr. Bream described at the preliminary hearing, indicated that he “was duly authorized. And if alcohol was going to come in, he had a duty to act as chaperone.”

Ms. Powers, the Penn State spokeswoman, would not answer whether the university told Mr. Bream to testify, but she did write in an email: “The University, through its legal counsel, communicated to Mr. Bream that he should accept service of the subpoena and appear in court.”

And while Mr. Bream was not charged in the criminal case, it is clear he is a focus of the Piazza family, which has called for Penn State to fire him.

“While it does not excuse the bad conduct of others, Bream is an important person in this matter,” Mr. Kline said. “We’ve always thought that.”

He is also a focus of one of two lawsuits brought by Donald Abbey, a wealthy Penn State and Beta alum who funded a $10 million renovation of the Beta house and who insisted on the installation of the surveillance cameras that captured the images of Mr. Piazza’s hazing and injuries.

Mr. Abbey had the cameras installed as a way to enforce the fraternity’s ban on alcohol in the house and ensure the house was not damaged. In one of his lawsuits, he is suing the housing corporation board of directors, which includes Mr. Bream, because he believes the events that led to Mr. Piazza’s death trigger a provision of his funding that means the fraternity has to pay him back.

Matt Haverstick, the attorney representing Mr. Abbey, would only say: “I’m looking forward to Mr. Bream’s deposition.”

Sean D. Hamill: shamill@post-gazette.com or 412-263-2579 or Twitter: @SeanDHamill