Through four crisp fall seasons at Pemberton Township High School, not many shots got past soccer goaltender Tommy Ayrer.

Nimble and quick-thinking, Tommy so stingily defended the Hornets’ net, he started at the position throughout his high school career. But in an unlucky instant, that career came to a sudden halt.

During a game in his senior year in 2013, Tommy collided with another player, taking a visibly nasty knock to the head. His mother, Karen Ayrer, took him to an emergency room.

There, she recalled, she was told Tommy was fine. Satisfied with the diagnosis, she was shocked when school athletic trainer Eileen Bowker refused to allow him to return to play.

Undeterred, Karen Ayrer took her son to a pediatrician, who also cleared him to play. Again, Bowker refused to follow suit.

Tommy needed to undergo testing and a more stringent protocol before returning even to the practice field, she insisted. And that testing revealed he had, indeed, suffered a concussion, school officials found.

“I was aggravated,” Karen Ayrer said. “I was livid, and he (Tommy) was livid. … I’m thinking, if a doctor says my kid doesn’t have a concussion, he doesn’t have a concussion.”

She appealed to other school officials, and Tommy repeatedly asked to be put back in, to no avail. Frustrated, they eventually gave up. Tommy would undergo further evaluations and rest time, as required, before finally being cleared to return.

“I’m pretty sure he sat out for a good eight to 10 games,” Karen Ayrer said.

Convinced that Bowker was being heavy-handed, the mom felt the resentment simmer. Ayrer never thought that two years later, she would thank the athletic trainer for her resolve.

After all, it just may have saved her son’s life.

Karen Ayrer was just one of many angry parents to whom Bowker has stood up to in her 30 years as an athletic trainer.

As in the Ayrer case, many protest her decisions not out of apathy toward their children’s health, but out of ignorance as to how cautious they must be in detecting a concussion and how drastic the consequences can be if an athlete returns to action too early after suffering one.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of 2010, at least 3 million sports- and recreation-related concussions occurred each year in the United States.

A concussion occurs when the brain is jolted by a blow to the head or neck, or even a jolt to the body overall. It may cause bruising, damage to blood vessels or nerve damage.

A person does not have to be knocked unconscious to suffer a concussion, and may not remember if he or she did lose consciousness.

A concussion can result in impaired mental and physical function that can continue for a wide range of time. Symptoms include headache, a feeling of pressure in the head, confusion, amnesia of the time surrounding the injury, nausea, fatigue, vomiting, slurred speech and others.

A victim may also suffer from depression, concentration or memory difficulties, irritability and other personality changes, sleep problems and other issues.

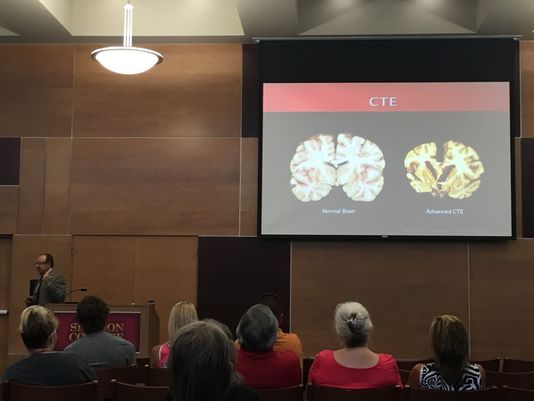

Repeat concussions can cause longer-term or permanent mental and cognitive problems. Returning to play too soon after a concussion presents the risk of second impact syndrome, a severe condition caused by a second concussion that occurs before the first one has properly healed.

Second impact syndrome can result in severe brain swelling, brain herniation, and other problems that greatly increase the risk of death.

That’s why New Jersey law mandates that any student suspected of having suffered a concussion must be sidelined and cannot return to activity until cleared by a doctor trained in evaluating and treating concussions.

A new bill introduced in the Assembly on Feb. 4 would require a public school student suffering a concussion to be cleared by such a doctor to return to school altogether. The bill has been referred to the Assembly Education Committee for consideration. The Senate version has passed that chamber’s Education Committee and will move on to a second reading.

Sidelined, for as long as it takes

School officials throughout Burlington County and well beyond have buckled down harder than ever in recent years in spotting concussions and other head injuries when they occur, and keeping players sidelined for as long as it takes.

High schools, including Pemberton Township, require all student athletes to undergo baseline testing, an evaluation of mental function under normal circumstances.

When a concussion is suspected, the student takes the same test, and the results are compared with the baseline to help determine if he or she is actually concussed. That’s just one of several tools trainers and doctors can use to make a diagnosis.

Another tool is the SCAT3 (Sport Concussion Assessment Tool-3rd edition), which is also used to help make a determination. The evaluation measures indicators such as memory, concentration, physical balance and coordination, among others.

Once a concussion is diagnosed in Pemberton Township, Bowker said, the student must complete several layers of requirements before returning to competition.

To start, she stresses that the student must rest, and that means real rest.

“That means no texting, no computer, no TV,” Bowker said. “Just really sleeping to let that brain recover.

“In my experience, those who really rest in the first 24 to 48 hours after a concussion end up returning quicker,” she said.

“For those who don’t listen, it’s not as good. Their headaches and other symptoms may get worse.”

Bowker said recovery time can vary widely. It can take a week, month, four months, even longer.

“Every concussion is so different, you really can’t give an average,” she said.

In any case, a student at Pemberton Township must be free of all symptoms for at least 72 hours before he or she can even think of returning to play.

“The student might start by riding an exercise bike or running on a treadmill or using an elliptical for a while, just to get the heart rate up,” Bowker said.

Another day without symptoms can mean some cardiovascular work or circuit training in the weight room, she said. And day three symptom-free could mean limited practice, without contact.

The following day, the student would take the baseline test. If the score is back to the original baseline, he or she then sees a physician, who must give the all clear for a return to play.

Precautions also go beyond high school. In February, the Marlton Recreation Council in Evesham, which runs 15 sports programs for kids, chose a local physical therapy provider to conduct baseline testing for 5,000 athletes.

M&M Physical Therapy administered the tests before the start of spring sports in March for children age 10 and older. The provider offered to test for $25, with part of the fee going back to the recreation council for sports programs.

M&M said it would conduct post-concussion tests at no cost.

The Burlington County Youth Athletic Association has also embraced the move toward greater concussion awareness.

While its coaches are already trained in state-mandated safety standards, the association is now going beyond that.

“With the help of the Willingboro Recreation Department, starting this season, all of our coaches and volunteers are required to undergo concussion training,” association president Chuck Esser said.

The organization offers baseball and softball programs for kids between 3 and 15. About 150 to 200 are registered, Esser said.

About 90 percent of participants are from Willingboro, he said, with the rest coming from neighboring communities like Edgewater Park and Riverside.

Media attention focused on the litany of health problems suffered by former NFL players has helped propel the treatment of concussions and other head injuries to the forefront of high school and youth sports.

Ex-players suffered from a range of conditions, including depression, early onset dementia and other psychological problems, with a number of suicides being blamed on complications from repeat concussions.

But reform efforts in Burlington County and elsewhere well predated the $1 billion settlement the NFL made with thousands of ex-players suffering from repeat brain injuries last year.

Pemberton Township instituted baseline testing in the early 2000s.

Concussions hit most sports

And while Americans tend to think first of the gridiron when they hear of concussions, Burlington County experts say the problem is widely distributed.

Bowker said just under 40 concussions were reported at her school last year. They spanned soccer, football, baseball, softball, tennis and cheerleading, she said, and soccer yielded more than football.

Mark Haines, athletic trainer at Rancocas Valley Regional High School in Mount Holly, said his school sees an average of about 25 reported concussions per year.

“It varies,” said the 34-year trainer, who is set to retire at the end of this school year. “We could have 29 one year and 24 the next. They’re mostly in football and soccer.

“This year, we had two cheerleaders suffer concussions,” he said. “We also had a tennis player and a volleyball player.”

Haines said many soccer concussions occur because of collisions. He and Bowker said cheerleaders may suffer them after bumping heads or taking an elbow from a teammate during stunts.

They can often occur as the cheerleaders are learning and practicing moves.

Paul Kasper, director of sports medicine at Virtua Health System, concurred.

“If you look at the physical conditioning of cheerleaders, they’re really pushing the boundaries of physical ability,” Kasper said.

“It’s pretty common when they’re learning, that they’re bumping heads. I think the challenges cheerleaders are expected to undertake are increasing,” he said. “They’re being asked to be more dynamic.”

Kasper said cheerleading is one of the sports, along with girls soccer, in which reports of head injuries are increasing.

“Historically, football, lacrosse, hockey and soccer have had higher rates of concussions,” he said. “Whenever those sports are in season, we see a general rise.”

Kasper said Virtua can receive reports of concussions in kids around 10-12.

“There’s a combination of reasons,” he said. “They’re starting to grow physically. As they enter puberty, they’re starting to grow bigger and stronger. But they can be uncoordinated early on, and collisions occur in which they injure themselves or their opponents.”

Bowker thinks back roughly two decades to when she worked as a trainer at Northern Burlington County Regional High School in Mansfield when she’s asked about how much attitudes have changed regarding head injuries in sports.

A football player there once visited the school nurse two weeks after a game in Delran with a bad headache, she recalled.

Perhaps his recollection of the game could help shed light on when and how his headaches had begun. The problem was he had no memory of the game.

The player later learned that, during the game, teammates had been picking him up and directing him to his place on the line of scrimmage after his injury, which turned out to be a concussion.

The case highlights the drastic turnaround in how head injuries are treated from the start. The contrast is seen in how a tennis player’s injury was addressed at Pemberton Township recently.

The girl was struck in the head by a serve from her teammate in a doubles match, Bowker said. She experienced common concussion symptoms — headache, nausea and loss of balance, among others.

As officials stuck to protocol in treating the injury, the student was out of school for about a week, Bowker recalled. She was out of competition for nearly nine months before she was functioning normally again.

‘It’s tough for the kid’

Haines, too, remembered the days when a player who took a hard hit or seemed dazed and confused was said to have been “dinged” or “had his bell rung.”

“They no longer say that,” he said. “If there’s any question at all of whether an athlete has a concussion, he or she is out and sees a doctor.

“It’s tough for the kid, because like any other injury, you tell him, ‘You’re done until you’re cleared to come back,’ ” Haines said.

“And that in itself is a bombshell for a kid, especially for varsity players, seniors, the upper-level players. If a kid is a No. 1 seed in a tournament, that’s devastating.”

But as thousands of former pro football players — and at least one grateful Burlington County mom will attest — it’s well worth it to sit out for a while.

Two years after she’d campaigned so hard to get her son back on the soccer field, Karen Ayrer learned that such a return could have been a terrible mistake.

Tommy, now a sophomore at Rowan University, had at times been slow to respond to her, she recalled, had issues with “spacing out,” as she put it, and had difficulty concentrating.

The issues may be due to what are known as silent seizures — not obvious all-out seizures — but short periods of blank stares potentially caused by abnormal brain activity.

While consulting a doctor on the issue, the question arose, “Has Tommy had any concussions?”

The question alone was an epiphany for Karen Ayrer, but it also posed a more frightening question: What if Bowker had relented and let Tommy back on the field?

She recently apologized to Bowker for her resistance, admitting that the staunch trainer had made what could have been a critical call.

“If he had been put back in, he might not be here today,” she said.

Karen Ayrer added that she now defends Bowker against parents angered when their children are taken out of competition because of head injuries.

“Parents have to listen to the athletic trainers,” she said. “She (Bowker) is making them sit because she wants them to live. And if she let them play, and something happened to them, she would never forgive herself.”