On a late August night in Chelsea, there were two football scores of note as visiting Northview High School collided with Chelsea High. There was the final tally, which after the usual assortment of helmet-smacking hits stood at: Chelsea 27, Northview 14.

But along the sideline, Jesse Brinks, the athletic trainer for Northview, a school north of Grand Rapids, was focused on a second set of numbers. Brinks handed an iPad to a Northview defensive back who just absorbed a hard blow while making a tackle. The player was asked to track a series of single-digit numbers on the screen. His score would give Brinks a good idea if the boy had a concussion.

In this case, he passed – and after clearing other tests, the player returned to the game in the second half.

Brinks guessed he’s used the test about 10 times this season, confirming a concussion in one case for a cheerleader who took an elbow to the head as she spotted for another cheerleader. In two other cases, it helped confirm concussions in football practice. “It’s a great tool for us,” Brinks said.

Amid growing fears nationally about the risks and long-term impact of concussions in sports, Northview’s sideline protocol is part of an ambitious pilot program in Michigan launched in August for 10,000 athletes in 70 public and private high schools.

According to the Michigan High School Athletic Association, it is the first of its kind in the nation. The association contends that Michigan is also first to require member schools to record suspected concussions in practice and in games at middle and high schools across the state.

“We’re trying to be on the front line, to make sure we’re doing everything we can to make sure our kids are safe,” said Northview athletic director Jerry Klekotka.

“I think it’s definitely a good direction to go. The safety of the players has to be number 1.” – Nate Moore, coach of Ohio football powerhouse Massillon Washington High School, on Ohio’s move to limit full-contact practice time.

That may be. But while Michigan appears to be ahead of the curve in how closely it tracks concussions, Bridge found that Michigan is behind many other states in limiting time young players can engage in full-contact practices during the week. Michigan, for instance, allows six times as much full-contact football practice each week as in the neighboring states of Wisconsin and Ohio.

These and many other states are sharply limiting full-contact scrimmaging in the face of research showing the routine, daily collisions in sports such as football or soccer can alter the brains of athletes, even when players are not specifically diagnosed with a concussion. Repeated, sub-concussive blows from full-contact scrimmages and games can have a significant impact over time. Other research has found that the risk of brain trauma to young players can commence well before high school.

“Common sense tells you that bopping your head all the time for a number of years is not going to be a good thing,” said Larry Levenerz, a Purdue University clinical professor of health and kinesiology and member of the school’s Purdue Neurotrauma Group, which has studied the effects of football on cognition since 2009.

More attention, more warnings

Warnings over the risks of football have been building by years, as events like the 2012 suicide of ex-NFL linebacker Junior Seau cast the issue into sharp national focus. An autopsy found that Seau suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a progressive degenerative disease linked to repetitive brain trauma, often marked by depression and cognitive deterioration. CTE, which can only be detected by examining the brain after death, has been found in dozens of former NFL players.

In September, researchers at the Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University found that 87 of 91 deceased NFL players whose brains were tested had evidence of CTE (That percentage is likely skewed since many of the players suspected they had CTE and asked that their brains be tested after they died).

But the disease is not limited to 30-something NFL veterans.

The same year Seau died, Joseph Chernach, who had played football since he was a young boy and became an Upper Peninsula high school football star, killed himself at age 25. An autopsy found significant evidence of CTE and brain damage. His mother, Debra Pyka, said he never had a confirmed concussion.

Mounting evidence of the dangers of repeated head contact has caused state bodies that regulate high school sports to reconsider how much contact should be permitted in practice. The era of hours-long, full-contact practices throughout the week appears to be on the wane, even in football factory states such as Ohio.

In July, the Ohio High School Athletic Association adopted guidelines aimed at curtailing hits during practice. It now limits schools to no more than two 30-minute, full-contact football practices a week. The Ohio change was driven by research showing that 58 percent of concussions among high school and college football players occurred in practice, compared with 42 percent in games.

More coverage: From high school football star to ‘a completely different person’

Nate Moore, coach of perennial Ohio football powerhouse Massillon High School, told Bridge he considers the movement to curb full-contact at practices a positive step.

“I think it’s definitely a good direction to go. The safety of the players has to be number 1,” Moore said.

Moore added that he doesn’t believe the restrictions will limit his ability to prepare his team to play its best football. “I don’t feel it’s negative at all,” he said. “The days of hammering ourselves in two-a-days (practices) in the summer are done.”

Wisconsin also limits full-contact practice to 60 minutes a week, after the first three weeks of practice and games. Other states, including Alabama, Iowa, Kansas, Georgia, Texas, California and Tennessee limit practice contact to 90 minutes a week. In California, that limit was imposed not by a high school athletic association, but by the state legislature, and was then signed into law last year by Gov. Jerry Brown.

According the National Federation of State High School Associations, there is evidencethese limits “resulted in a statistically significant decrease in concussion rates during practices.”

More hitting in Michigan

By contrast, Michigan allows two full-contact practices a week after the first game of the football season – with a maximum length of three hours per practice, for a total of six hours a week of hitting. That’s six times what Ohio and Wisconsin allow.

Even that six-hour restriction, adopted in 2014, met resistance from some old-school Michigan coaches.

Tom Mach, a 10-time state champion and for 27 years head coach at Detroit Catholic Central, was quoted at the time saying the six-hour limit would make it harder to teach proper tackling techniques.

“When they get into the game, it has to be an automatic thing,” he said. “The more time we take away from being able to teach that (in live game speed), the worse results we’re going to get.”

The recent focus on concussions and player safety seems to be giving some parents and players second thoughts about playing tackle football. The number of participants in Michigan high school football has declined seven straight years. It’s also changing the way football is being taught, with coaches from youth leagues to the NFL focusing on safer tackling techniques that cut down on helmet-to-helmet contact.

Other sports too are paying attention. Safety advocates in sports like soccer have begun to question whether young players should be allowed to “head” the ball, a routine skill taught to players but one that is also linked to concussions.

But no sport features as many opportunities to knock heads as football.

Hundreds of blows

The 2012 Purdue University study, which tracked a couple dozen high school football players over the course of two seasons, found that players logged anywhere from 200 to1,800 hits to the head over the course of a season. MRI tests found that 17 players – who wore special helmets equipped with sensors – had measurable changes to their brain, with the magnitude of change to brain activity corresponded with the number of hits the player took. None of the players logged having a concussion.

Leverenz, of Purdue, said it’s unclear at what point the cognitive changes documented in these studies will lead to serious impairment. He said the group’s research is finding that the football players’ brains – though changed – can essentially rewire themselves, finding new neural tracks, so that outward cognitive functioning seems the same. “At what point,” he asked, “do enough of these (neural) tracks get damaged?”

John E. “Jack” Roberts, the executive director of MHSAA, which has a voluntary membership of over 1,500 public and private middle and high schools in the state, said he believes most Michigan schools conduct full-contact football practices that are considerably shorter than the two three-hour practice maximums allowed.

But given the steps taken by other states to more strictly limit full-contact practice, Roberts acknowledged to Bridge that it’s an issue his organization should reconsider. That decision would be made by its 19-member governing board, which is next scheduled to meet in December.

“We don’t want to be behind that curve,” Roberts said. “Now we can go back and revisit this to see if there is some tweaking we should do.”

In the meantime, research on head trauma in sports is finding that the risk of injury can begin as young as age 5, the minimum age to participate in Pop Warner youth football:

A 2013 study of football players ages 9 to 12 in the Annals of Biomedical Engineering found that the players averaged 240 high-magnitude hits in the course of a season between practice and games.

Another study in the Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics found that one-in-30 football players ages 5 to 14 will sustain one concussion per season.

Other sports taking notice

Studies of young soccer players are detecting brain changes from the repetitive heading of the soccer ball, regardless of whether concussions were reported. A 2013 Texas medical study of 24 teenage girls found indications of “cognitive dysfunctions” in half of them from heading the ball, compared with none recorded among 12 non-soccer players.

Such findings prompted a group of World Cup soccer stars in 2014 to call for a ban on heading the ball until age 14.

In May 2014, a Pennsylvania middle school decided to ban heading in middle school soccer in the 2015 season, perhaps the first school in nation to do so.

Roberts of the MHSAA said he has been pushing member schools and coaches to consider a similar ban on heading in middle-school soccer, perhaps junior varsity as well ‒ thus far to no avail.

“The purists think that’s the end of soccer,” Roberts said.

Given the nature of football, it’s no surprise the sport leads the ways in the risks posed by concussion. But it’s not alone among high school sports.

According to a report by the American Journal of Sports Medicine, football had an average rate of 64 concussions per athlete per 100,000 games or practices in 2008 through 2010.That was followed by ice hockey, at 54 per 100,000, boys’ lacrosse at 40, girls’ lacrosse at 35 and girls’ soccer at 34.

But with some 40,000 players, far more than any other high school sport in Michigan, football leads the way in concussions. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control estimates there are more than 25,000emergency room visits a year for traumatic brain injury among football players under age 19, second only to bicycling among all sports and recreational activities as a cause of head trauma.

The sweet science

To be sure, it’s not as if sports like football and soccer suddenly became dangerous.

Boxing had been known to cause what is now known as CTE since the 1920s, an era when ex-fighters were commonly described as “punch drunk.”

But in 2005, a forensic neuropathologist published findings on his examination of the brain of former Pittsburgh Steeler linebacker Mike Webster, who died in 2002 with severe dementia. He concluded Webster had CTE ‒ the first time it was confirmed in an NFL player.

A 2015 Boston University study of former NFL players concluded that the risks to cognitive functioning rise the longer an individual plays football. Players who began football before age 12, had “greater later-life cognitive impairment” as measured by a battery of cognitive tests, the study found.

By then, states, including Michigan, were taking notice.

In October 2012, Gov. Rick Snyder signed legislation that requires coaches to remove any youth athlete suspected of a concussion. Players removed cannot return to competition without written clearance from a health care professional. It is similar to legislationpassed by all 50 states since 2007.

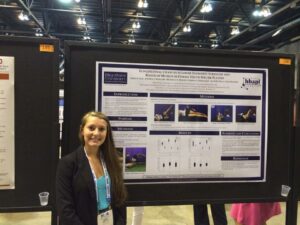

It’s the hope of the MHSAA pilot study to take diagnosis of concussion to a more precise level.

Participating schools use one of two devices to gauge concussion, taking baseline cognitive results from before the season begins to compare with results in practice or competition. It is to be used for two sports each season for both boys’ and girls’ sports, ranging from football to hockey to soccer to volleyball – and yes, cheerleading.

The system used by Northview High School, known as the King-Devick test, compares the baseline ability of an athlete to rapidly repeat single-digit numbers on a computer screen to results recorded after a suspected concussion. The test detects impaired rapid eye movement, attention and concentration that are symptoms of concussion.

Other schools are employing a program called XLNTbrain Sport, which assesses an athlete’s balance and cognition using a smartphone or tablet, comparing the result in competition or practice with baseline scores.

Giving parents pause

In the meantime, it may be the concussion issue is eroding participation in high school football.

According to the MHSAA, the number participants in 11-player football fell 15 percent in Michigan between 2007 and 2014, with declines each of the last 8 years. That exceeds an 11 percent decline in boys attending MHSAA-member schools over that period.

Despite the parade of scary headlines, Northview athletic director Klekotka said he believes recent changes in the way coaches teach football fundamentals is making a positive difference. Northview is in line with many other schools in putting greater focus on tackling without using the crown of the helmet to bring a player down.

In 2012, the NFL endorsed this approach, called Heads Up Football, geared to encourage coaches from youth through high school to teach this technique. Michigan State University football coach Mark Dantonio has even begun teaching players rugby tackling techniques in an effort to reduce the percentage of head-first strikes.

“I think football is safer than it has ever been,” Klekotka said.

Brinks, the trainer, has twin 5-year-old boys, Samuel and Mason, who he says are just becoming aware what the sport of football is about. Though he’s seen his share of concussions, Brinks said he won’t stand in their way if they want to strap on a helmet in a few years.

Brinks still views the sport as relatively safe, and one that builds important qualities of teamwork and leadership.

“I do think the positive life lessons learned through competing in football outweigh the negative consequences. If they want to play football,” he said, “I would support that.”

ORIGINAL ARTICLE:

http://bridgemi.com/2015/10/despite-concussion-fears-michigan-allows-long-hours-of-prep-football-hitting/