Article reposted from The Albuquerque Journal

Author: Joline Gutierrez Krueger

He knew what he wanted.

Other kids in younger years had toyed with conventional ideas of what they wanted to be when they grew up – a firefighter, a doctor, a police officer, a nurse – but as teens they felt little pressure to decide which career path to choose.

JT Gallegos just knew.

He had always known, at least as far back as he can remember, at least as far back as that moment he threw his first football – which, his mother says, was about the same time he learned to walk.

“Since he was little, he has lived and breathed football,” grandmother Liz Martinez says. “JT plays basketball, too, but for him it was always football.”

Maybe that’s not surprising for a kid who grew up – way up – as the tallest and biggest kid in the class. He seemed made for the sport.

Sometimes, though, things don’t go as planned. Sometimes, the path we choose takes an unexpected turn.

So it was for JT. He’s 15 now, a hulking 6-foot-4, 200-pound sophomore on both the Rio Rancho High School junior varsity and varsity teams. On Sept. 25, he played his last game ever.

No one had seen that turn coming.

It was the fourth quarter of a home JV game against Volcano Vista High School, and the Rio Rancho Rams were down 32-47. JT had the ball and was running it back after a kickoff when he was tackled.

It wasn’t a particularly harsh tackle, as those things go, but it left JT feeling dizzy and his head hurt.

Still, when it was time to get back onto the field, he did.

That’s when he blacked out, clutching onto a teammate to help soften his fall facedown on the field.

He couldn’t move.

Parents Angie and Jason Gallegos and grandmother Martinez watched with horror in the stands.

“We were confused because there wasn’t a play,” his mother says. “We didn’t know what had happened to make him fall like that.”

As a young player, JT had been taught that unless he was really hurt he needed to “pop up” from the field right away after being knocked down so as not to freak out his mother.

This time, he couldn’t. And his mother freaked out.

“I kept saying, ‘He’s not popping up! He’s not popping up!’ ” she says.

So she did, racing down to the field with her husband not far behind.

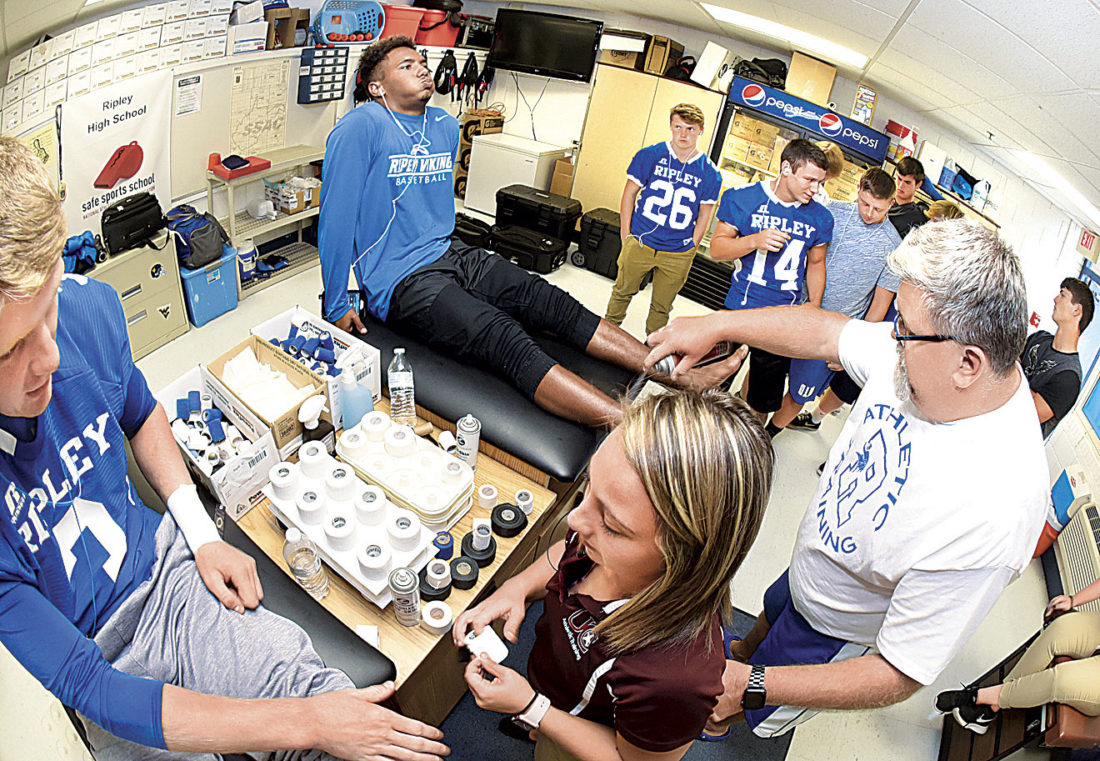

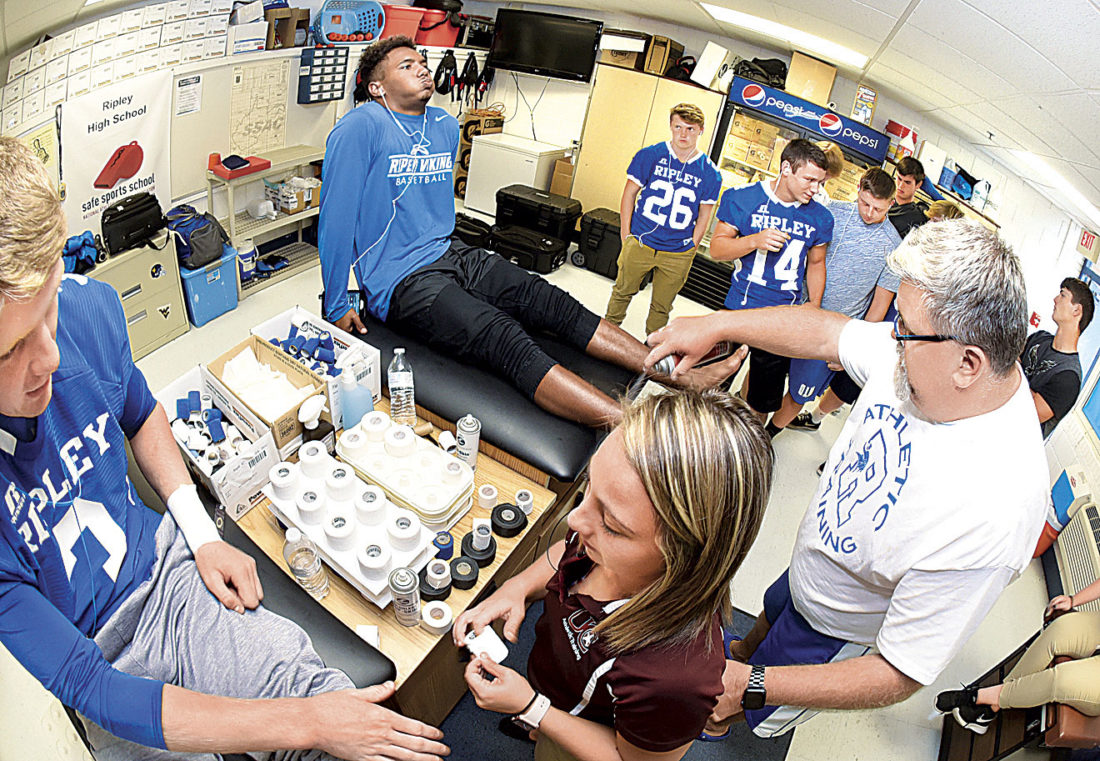

As she made her way down, coach Jason Vance and athletic trainer Colby Aragon were gently easing JT onto his back. What they saw caused them to immediately grab their cellphones.

JT was taken by ambulance to Presbyterian Rust Medical Center in Rio Rancho, where for four hours he was unable to move more than a slight wiggle of a toe or a finger. His mother held his hand and tried not to cry.

In the hospital waiting room, dozens of football players, most still in their jerseys, the coaching staff, family and friends tried not to cry, too. They prayed.

By morning, TJ had regained his mobility, his injuries likely the result of a severe concussion and a spinal neck sprain from the previous tackle – or so his family thought.

After TJ was transferred to the University of New Mexico Hospital, further testing revealed a diagnosis that was far worse – os Odontoideum, a rare condition in which a small finger-like projection, called the odontoid process, from the second cervical vertebra in the neck is missing or malformed. The odontoid process keeps the first vertebra aligned and able to pivot. Without it, the underlying spinal cord is at risk.

So insidious is the condition that it is typically not diagnosed until after the patient is permanently paralyzed or dead.

“The surgeon says it was a miracle we found it this way,” Angie Gallegos says. “They’re surprised something worse didn’t happen sooner, given the sports JT has played.”

But, oh, what a cruel twist. That last tackle likely saved JT’s life, but it also took away a large part of it. Because of his condition, doctors have told him he must never play contact sports.

That includes football.

That, his mother says, has been hard to take. A teenager with his feet already firmly on a chosen path is not easily consolable.

“It hurts to think he will never step out on that field again,” she says. “We keep telling him God has a better plan for him. But right now it’s hard for him to see past football.”

This Sunday, a fundraiser featuring food and football will be held for JT and his family to defray medical costs. The JT Gallegos Youth Football Jamboree, as the event is being called, will feature four games between teams in the Northern New Mexico Children’s Football League, including the Punishers, the name of the team JT played on in his younger days.

Weeks from now, he will undergo a procedure to have his top two vertebrae fused together to stabilize his spine. Surgery is set for Nov. 22, the day before Thanksgiving.

Until then, he must wear a neck brace, even when he sleeps and showers.

He did not want to talk for this column.

He has lost what he wanted, but he still has the movement of his hands, the stride of his legs, the spirit of a champion, even though it may not feel that way just now.

What he still has is a life upright and time for new dreams, a new path. Someday TJ will know that. He will just know.

UpFront is a front-page news and opinion column. Comment directly to Joline at 823-3603, jkrueger@abqjournal.com or follow her on Twitter @jolinegkg. Go to www.abqjournal.com/letters/new to submit a letter to the editor.