Article reposted from Valley News

Author: Tris Wykes

Fred Kelley’s smile was dazzling, and he flashed it often.

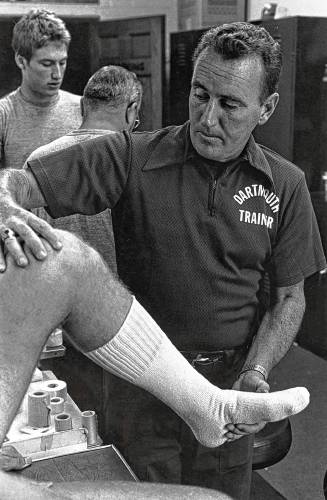

Dartmouth College’s head athletic trainer was in the serious business of preventing and treating injuries, but he knew that laughter, a grin, and a funny anecdote could go a long way in his line of work.

Kelley, who served Dartmouth in that role from 1967 to 1994 and doubled as a Big Green baseball coach during the 1970s, died May 11, 2017, in Kissimmee, Fla., of congestive heart failure and after battling kidney cancer. To the end, however, he believed he would pull through, his optimistic attitude a reason why he reached an eighth decade, his two children said.

“He was bedridden but convinced he was going to make it to the next doctor’s appointment,” said his daughter, Kristen Kelley, a Hanover High and Dartmouth graduate who often had to collude with her father’s friends to discover his true condition. “He was a former Marine and tough as nails and he didn’t want to put anybody out.”

Kelley faced a staggering number of challenges and virtually all of them with good cheer. A native of Gloversville, N.Y., an hour’s drive northwest of Albany, he endured a childhood laden with poverty and abuse, as well as the death of his first wife. He suffered three heart attacks, two forms of cancer, a pair of back operations, hand surgery and overcame alcoholism.

“I will never forget the long nights in the intensive care unit when it seemed the morning would never come,” Kelley wrote in a family history he compiled for his grandson, 2017 Sharon Academy graduate and current Emerson College freshman Harvey Kelley.

Said Kristen Kelley: “A lot of people in his situation would wind up being introverts or bitter, but he had a zest for life.”

Kelley was the younger of two sons born to John and Helen (Enser) Kelley in Broadalbin, N.Y. His father was killed in a 1937 car crash and Helen Kelley later married widower George Brennan, who had four children of his own. The couple established a grocery store in Johnstown, N.Y., and lived above it until declaring bankruptcy in 1938. The family’s situation grew so dire that it was forced to split up and only Fred stayed with the Kelley parents.

Harvey eventually moved back home and Grandmother Enser soon moved nearby and sometimes hosted them for Saturday night sleepovers. If she was in a good mood, they could expect car trips, boat cruises, candy and to play board games before being read aloud Tarzan and Hardy Boys books in their pajamas.

On darker occasions, however, the older woman would verbally abuse the brothers. She made them clean a textured tin ceiling with a toothbrush while perched atop stepladders, struck them with a metal vacuum cleaner wand and forced them into scalding baths, Kelley recalled in the family history. He attributed his grandmother’s behavior to grief at her husband’s death.

“I remember to this day, going to bed with blisters on my rear end and groin,” he wrote.

Fred Kelley mirrored his brother’s passions for sports and music. The younger boy would pitch for hours to his older sibling and they performed in barbershop quartets, a dance band and drum and bugle corps together.

Kelley arrived at Springfield (Mass.) College short on money needed for the $950 annual tuition but negotiated a payment plan to become a physical education major. He paid the remaining bill and supported himself by singing in two church choirs, writing for the sports information department, acting as a dorm trunk-room attendant and as test subject for college research experiments.

“When anyone would ask me what I’d had to eat that day, I would tell them a roll for breakfast, some water for lunch and swelled up for dinner,” Kelley wrote. He sometimes survived on a single packet of peanut butter crackers per day and collected empty bottles around campus, redeeming them for cash.

As sophomore, Kelley was a relief pitcher for the Indians baseball varsity that reached the 12-team College World Series, losing to Oklahoma and Arizona. He also began receiving mysterious envelopes without return addresses but containing $10 here and $20 there. He used those gifts, the origins of which he never discovered, to pay for food and lab fees. In the summers, he worked at a series of resorts and camps, sometimes putting on water-skiing exhibitions and other times serving as a youth counselor.

Kelley’s financial situation was untenable by 1956 and he followed his brother into the Marines. While at radio school in Norfolk, Va., Kelley married Anita Bonuccelli of nearby Richmond. She fell ill en route to the couple’s honeymoon, however, and later died of a blood disease. Kelley was discharged less than a year later and returned to Springfield.

Kelley’s continued work at summer camps led him to cross paths with fellow staff member Susan Van Keuren, whom he’d later marry. First, however, he accepted a job to be an assistant baseball and basketball coach at Virginia Military Institute.

The gig paid $3,000 per year and Kelley lived in the bachelor officers quarters and ate in their mess hall, both for free. In addition to coaching, he taught physical education and oversaw the intramural program. He and Van Keuren became engaged during his first year at VMI.

The couple’s first child, Michael, was born in 1965 and life became even busier when Kelley took over as VMI’s head baseball coach for two seasons. He was offered the Keydets’ head job on the hardwood as well, but turned it down to devote more time to family, sports medicine and the pursuit of a master’s degree. He authored a book on training techniques and became an early practitioner of what would become known as physical therapy.

The head trainer’s job came open at Dartmouth in 1967. The move was appealing because Hanover was closer to couple’s extended families. Although Fred was making $12,000 annually at VMI and would have to take a pay cut at Dartmouth, he accepted its eventual offer.

The Kelleys arrived at what then-sports information director Jack DeGange described in an email as “something of a golden era in athletics at Dartmouth.” The Big Green won or shared five consecutive Ivy League football titles from 1969-73, the 1970 baseball team reached the College World Series, men’s basketball posted a couple of rare winning seasons and ice hockey was reviving in recently built Thompson Arena.

Many of the Dartmouth coaches and administrators were in their late 20s and early 30s and had school-aged children. Kristen Kelley recalls numerous athletics families gathering for a day of swimming in someone’s back yard. The adults would socialize and sing along to a guitar and the kids would run and wrestle and squabble and collapse for brief periods of rest.

“Everyone looked out for them,” Kristen Kelley said. “It was chaos.”

Wrote DeGange: “We worked together and partied together and built friendships… that have been enduring.”

At home, the Kelleys often ate dinner out of trays placed atop small folding tables in the den. Fred would don an old pair of sweatpants, announce that nothing on earth was going to get him out of the house that night, and the family would watch television shows that ranged from Bonanza to M*A*S*H and F Troop.

“Some of my earliest memories involve that room’s horrible, gray wood paneling and its plush red carpet,” Kristin Kelley said. “Mom and Dad would drink Manhattans on the rocks and she would do her crossword puzzle and I would sit at Dad’s feet. He was very content to be just settled and at home.”

Although the school year was consumed by sports, the Kelleys enjoyed summer sojourns at the Whip ‘O Will resort on Newfound Lake in central New Hampshire. Tiny cabins without air conditioning, meals in a dining hall, sing-alongs and banjo playing and campfires by the water — it all remains vivid in Michael and Kristin Kelley’s memories. Their father used to wolf down his dinner so he could pitch to any and all kids in Wiffle Ball and he eventually requested that his ashes be scattered on the lake, as Sue Kelley’s were done before him.

At Dartmouth, Fred Kelley rose from freshman baseball coach to the varsity boss in 1978 after the retirement of the legendary Ulysses “Tony” Lupien, a former Major League player who had been coaching the Indians since 1957.

Kelley sometimes had to make bus trips standing up front with the driver because his back wouldn’t permit him to sit for extended periods and his three varsity teams had a combined overall record of 19-84.

That was a busy stretch for Kelley, who worked at the 1980 Lake Placid Winter Olympics, primarily in the foreign athletes’ compound. The Dartmouth football team won Ivy titles in 1981 and 1982, two of the 11 such crowns Kelley experienced with the program.

The veteran “toe-taper” was inducted into the National Athletic Trainers Association hall of fame in 1989, five years before he stepped down at Dartmouth. Jeff Frechette, now the college’s head athletic trainer and a 1976 Woodstock High graduate on the job since 1981, said the honor was well-deserved.

“Fred was a pioneer in a lot of ways,” said Frechette, who credits Kelley with reinforcing his desire to become a trainer when he was a high school senior. “Guys like him were the first to be formally educated in our profession and to push it forward in terms of certification.

“His real strength, though, was that he’d help anyone who walked through the door and he was very good at explaining what they needed to do to get better. People were drawn to him because of that.”

Kelley continued to own a fully-stocked training bag during his retirement, a time when some people downshift but he seemed to hit the gas. A move to the Eastman golf community in Grantham during the 1990s was followed by a relocation to Solavita, a planned Florida community for adults 55 and older that’s an hour’s drive south of Orlando.

Sue Kelley, who had operated her own day care, worked at a bank and been an Avon representative during her Hanover days, passed away in 2005. By the time her husband turned 75, however, he had amassed enough friends in his new location that the guest list had to be capped at 80. He sang and danced in two musical groups and maintained a single-digit golf handicap.

He regularly returned to play in the Tommy Keane Invitational tournament he helped found at the Hanover Country Club, especially enjoying the chance to pair up with Michael, who’d gone on to compete as a rower at Maine’s Colby College.

Most tellingly, Fred Kelley maintained his willingness to listen to friends and strangers and try to alleviate their aches and pains. Whether wrapping a knee, dispensing fitness and rehabilitation advice or expertly rubbing a friend’s sore back, Fred Kelley genuinely cared. Late in life, he not only withstood a pair of heart attacks, he saved the life of a fellow chorus member by administering CPR after the man suffered one of his own.

“He was the predecessor to the (urgent care) clinic,” said Mike Kelley, who recalled Big Apple Circus ringmaster Paul Binder arriving unannounced and sore at the Kelley family’s Woodmore Drive front door one day. “He enjoyed people and being the reason they felt better, and when he smiled, people smiled back at him.”

Tris Wykes can be reached at twykes@vnews.com or 603-727-3227.