Article reposted from The San Diego Union Tribune

Author: P.K. Daniel

Last month, a spectator suffered a heart attack while attending a basketball game at Rancho Bernardo High.

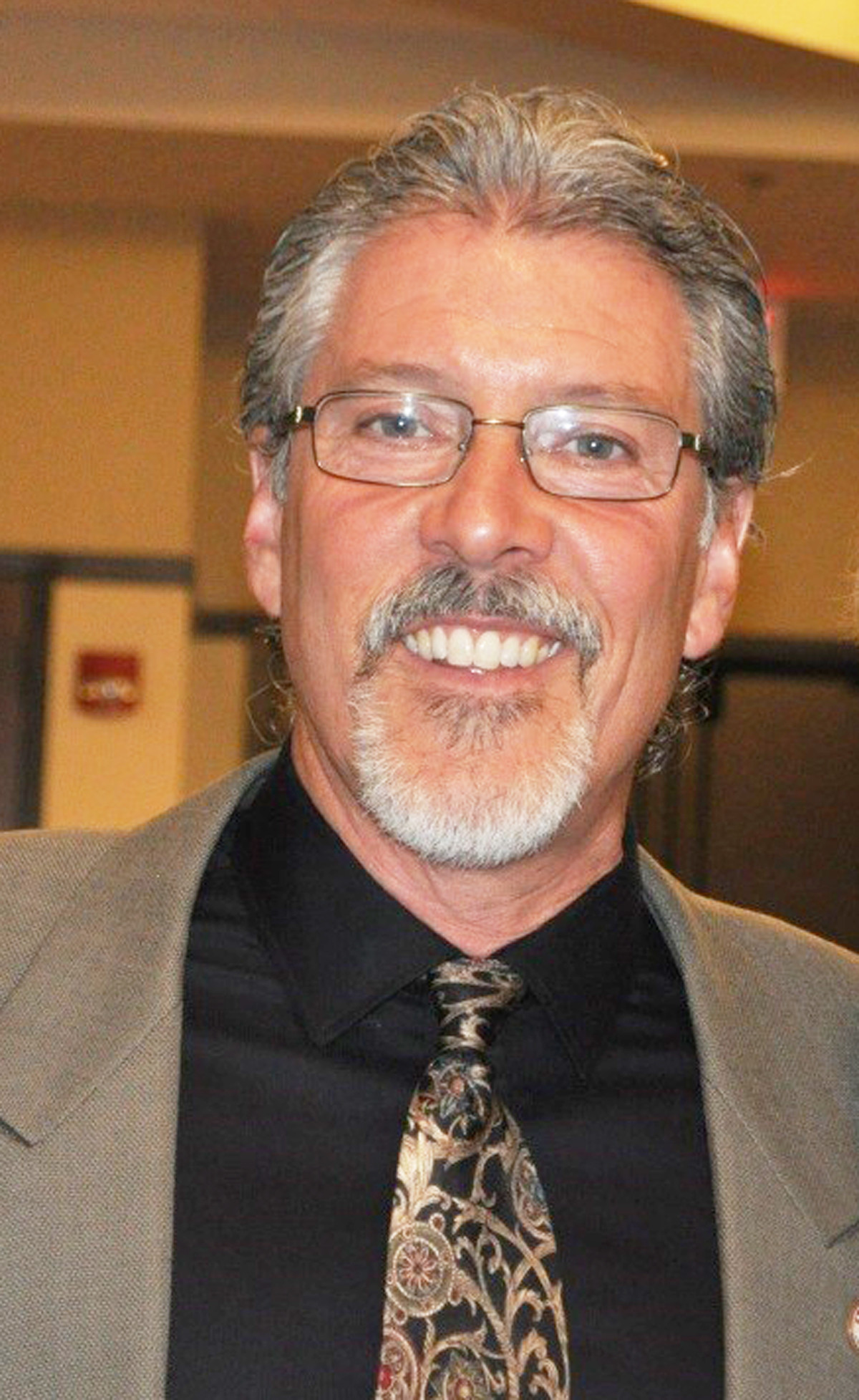

Robbie Bowers — the school’s certified athletic trainer, also known as an AT— was working the game. He and his staff put their emergency action plan into effect, utilizing the school’s defibrillator and CPR to save the elderly man’s life.

Unlike at Rancho Bernardo and other high schools in the Poway district, few student-athletes — let alone fans — in the CIF’s San Diego Section enjoy the safety and benefits of a full-time certified athletic trainer.

According to a 2015 story by CBS Sacramento, 80 percent of California high schools don’t employ full-time athletic trainers, whose job is to collaborate with physicians in providing preventive and emergency care, diagnosis, rehabilitation and other medical services.

Additionally, not all trainers are certified. And none are licensed in California.

“In California, anyone can say they are an ‘athletic trainer’ regardless of educational preparedness or skill,” said Tom Abdenour, longtime AT with the Golden State Warriors and former SDSU athletic trainer. “Needless to say, this can put a young student-athlete at risk if the wrong person does the wrong thing at the wrong time.”

California is the only state that does not recognize athletic trainers as licensed health-care practitioners. It doesn’t regulate the industry or define its scope of practice.

The California Athletic Trainers’ Association (CATA) has been campaigning for the passage of legislation since the mid-’80s. The most recent measure in 2015 would have restricted use of the title “athletic trainer” to only those individuals who have fulfilled the requirements for certification by a national body.

The bill had unanimous support in the legislature but was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown, who said certification imposes unnecessary burdens on athletic trainers without sufficient evidence that certain levels of education are needed.

As it stands, certification requires a bachelor’s degree with 70 percent of athletic trainers holding a master’s degree. According to Brown, the “burdens” outweigh the risk of having unlicensed trainers.

Mike Chisar is chairman of CATA’s Governmental Affairs Committee. He said the association has provided incidents of harm but pointed out the challenge of documentation since uncertified athletic trainers generally don’t keep medical records.

“You would hate for a kid to die to make (Brown) go, ‘Oh, there’s harm here or there’s the potential for harm by having somebody who’s not trained making (medical) decisions,’” Chisar said.

Alaska recently joined an increasing number of states (including Texas, Hawaii, Utah, Arizona, New York and Massachusetts) that require out-of-state trainers practicing in their state to be licensed, prompting new licensure legislation to be introduced this month in California.

The California Interscholastic Federation, the state’s governing body for high school sports, has safety guidelines on several issues. When it enacted concussion management and return-to-play protocols, it was complying with state law. But mandating full-time athletic trainers at every high school is beyond the CIF’s purview. Personnel and staffing decisions are under the local control of elected school boards.

Certification and licensing issues aside, a lack of funding is often cited as the reason ATs are not required.

“I think it really comes down to resources,” said Bowers, the outgoing secondary schools chairman for CATA. “In the past, I think there was confusion as to what an athletic trainer was/does, but I think through education that perception is becoming more clear and (schools) are desiring an athletic trainer. How to pay for it has become the bigger issue.”

Until this school year, San Diego Unified, the second-largest school district in California, did not have athletic trainers at each of its 16 high schools that have athletic programs. But district backing, including $416,000 in funding, allowed Scott Giusti, director of PE, health and athletics, to contract with UC San Diego to hire part-time certified athletic trainers.

“I cannot stress enough what a great thing this has been for our students and our schools,” Giusti said.

The CIF’s San Diego Section does ensure that athletic trainers are at most postseason competitions.

“At CIF events, we either require or provide trainers,” section Commissioner Jerry Schniepp said.

This year, the San Diego Section started a health and safety advisory committee composed of physicians, athletic trainers and school administrators.

“We are trying to provide for all schools a best-practices guideline on athletic training issues, head injuries, etc.,” Schniepp said.

San Diego schools and districts have dealt with the issue of athletic trainers in different ways. In 2015, CATA conducted a survey in which only 33 of more than 100 San Diego Section schools participated. Ten schools had no athletic trainer, six had an uncertified athletic trainer and 17 schools had at least one certified athletic trainer. Chisar said the employment status ran the gamut from attendance at football games only, to part time to full time. In the San Diego sample, 13 trainers were full time, eight were part time and two were football only.

The Grossmont district allots $10,000 to each of its nine comprehensive high schools as part of the annual athletic trainer budget, allowing each school to hire a part-time trainer.

“We strive to hire certified athletic trainers,” said Brian Wilbur, director of athletics for the Grossmont district. “In many cases, the trainer is also a teacher at the school or holds another classified position.”

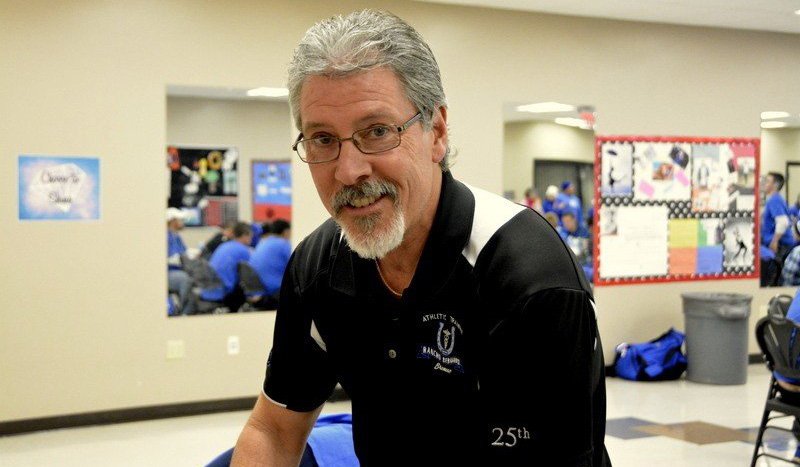

Sweetwater Union has placed full-time certified athletic trainers at eight of its 12 high schools, and expects to have all 12 staffed next year. The trainers teach sports medicine and physical therapy classes during the day. Their remaining hours are devoted to athletic training.

Helping to implement the program was Dr. Charles Camarata, who has devoted many years to helping South County high school athletes.

Said Camarata: “The district is on board and sees the value.”