Article reposted from UNLV

Author: BENJAMIN GLESSIER

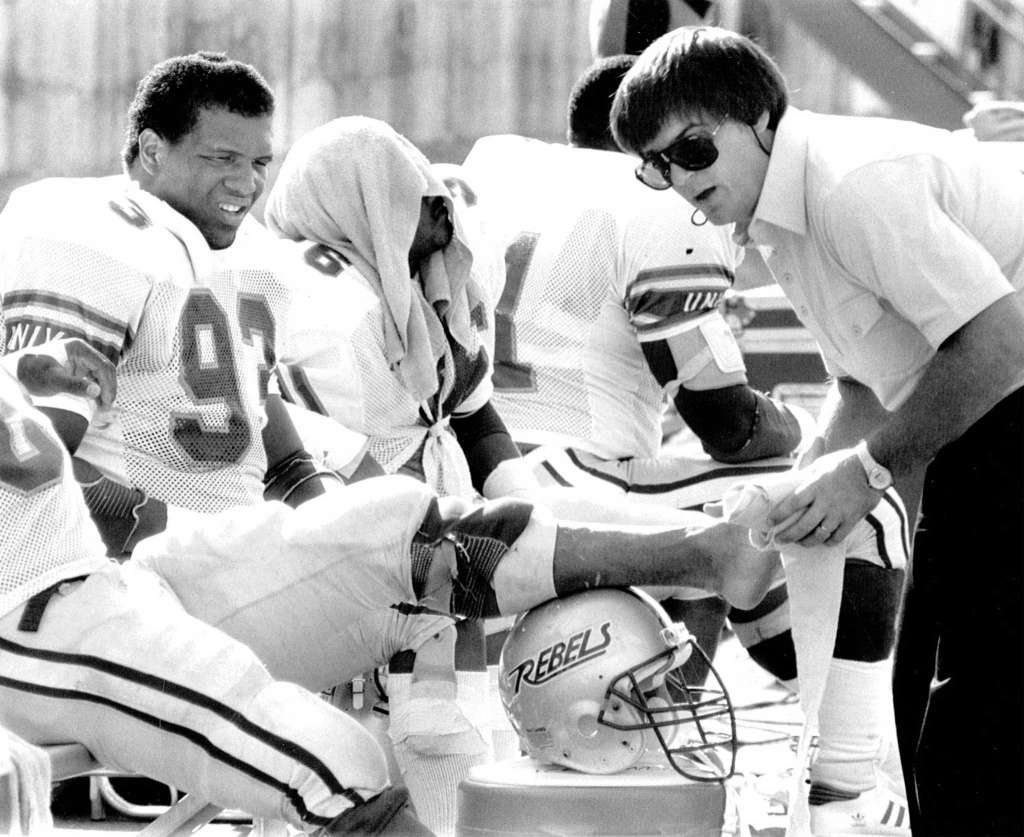

Think of athletic trainers as the team behind the team. When a baseball player turns an ankle on a hard slide into second base or a football player has a neck spasm after a hard tackle, they turn to their team’s athletic trainers. Their job: Get players back into the game.

Seattle Mariners assistant athletic trainer Rob Nodine, ’92 B.S. Athletic Training, summed it up this way: “If the players are doing well, that means we’re doing well.” Trainers, he added, “don’t like to be in the limelight.”

Nodine, and several other trainers in professional sports, learned how to do just that through UNLV’s athletic training program, which has seen at least 10 graduates hired by professional teams in the last 12 years.

Dallas Cowboys physical therapist/assistant athletic trainer Hanson Yang, ’09 M.S. Kinesiology, most commonly helps players come back from the collarbone fractures and shoulder dislocations. Neck injuries, he said, are the most challenging.Hanson Yang, ’09 Kinesiology, is an assistant athletic trainer for the Dallas Cowboys, where he helps keep players on the field through collarbone, shoulder and soft-tissue injuries.

“There’s not a lot we can immediately do with a neck injury, so we make sure the player is OK first,” Yang said. “But what’s most gratifying is when I work with a player who has experienced a soft-tissue injury before halftime, then I get him into the locker room for some work and 15 minutes later, he’s able to go out and play again.”

Likewise, Boston Red Sox assistant athletic trainer Masai Takahashi, ’99 B.S. and ’03 M.S. Sports Injury Management, is familiar with the aches and pains a hurler can experience over the course of a 162-game season. He was a pitcher on his high school baseball team in Japan.

“Most of the injuries I see are overuse injuries — stiffness in the shoulders, back strain — because the muscles get tight,” he said. “I try to catch tightness before it becomes an injury, so I do a lot of soft-tissue work on players to keep their muscles loose.”

Pitchers are always his biggest challenge. Almost no starter makes it through a season of 35 to 40 appearances throwing a baseball more than a hundred times a game without feeling some muscle fatigue, Takahashi said.

“If we can help them get through the season without going on the (disabled list), that’s very satisfying for us.”

At UNLV, they all became well trained in manual therapy, a technique in which they probe for and treat injuries with their hands. “There are things you can feel by hand that you won’t pick up in an X-ray or an ultrasound,” Takahashi said. “Every athlete is different, and it’s important to not only learn the difference between each athlete, but how each athlete’s body feels from day to day. That way, you can be proactive and prevent injuries.”

“Every player has his own driving force,” Nodine said. “We pay attention to players’ needs on a daily basis because knowing how injuries play into their psyche is very important. Athletes want to keep playing at a very high level of performance, and they like it when we explain things to them.”

Seattle Mariners assistant athletic trainer Rob Nodine, speaks with pitcher Felix Hernandez during a game.

Nodine, who served on the Professional Baseball Athletic Trainers Society’s executive committee from 2010-15, credited Kyle Wilson, UNLV assistant athletic director for sports medicine, for teaching him about the emotional component of athletic training.

Athletic training students typically spend mornings in the classroom learning the fundamentals of health care, then work with university teams in the afternoon to get invaluable real-world experience. The regimen has led to a first-time pass rate average of 98 percent on the national certification exam since 2010 – well ahead of the three-year national average of 81 percent.

“It’s common sense to know that everyone handles pain and healing different,” Wilson said. “Two different baseball players might have the same injury, but they’ll respond to treatment differently. That’s why it’s important to interact with athletes when they’re not injured.”

After NFL Draft Day, Yang spent the summer immersing himself in learning about Taco Charlton and the Cowboys’ new recruits. He and his fellow trainers developed exercise regimens for players at a series of mini-camps that will help the coaches winnow down the aspiring NFLers to a final roster of 53 players before the season kicks off.

The camps also give Yang a chance to build trust with the athletes he’ll be caring for all season. He asks about their families and lives outside of sports.

Yang had planned a career in engineering until he shadowed a family friend tending to a sports team. “I never believed I’d get to this professional level,” Yang said. “I appreciate my instructors, who taught me how to develop a good rapport with athletes, and to really understand that they are individuals, not just protocols. They gave me the opportunity to assess and develop treatments for patients, and then give me the confidence to use those skills on my own.