Article reposted from San Francisco Chronicle

Author: Al Saracevic

As the sun sets and the Friday night lights go on at football fields across California this week, thousands of high school players will prepare to clash.

In the stands, proud parents will look down on the field nervously, outwardly willing their sons to succeed while inwardly praying for their safety.

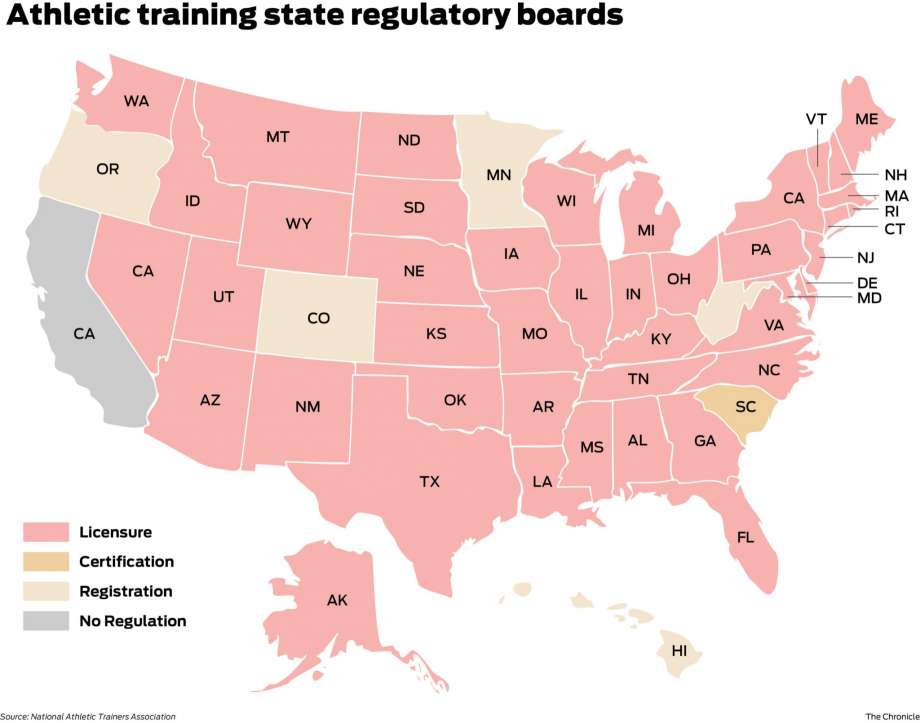

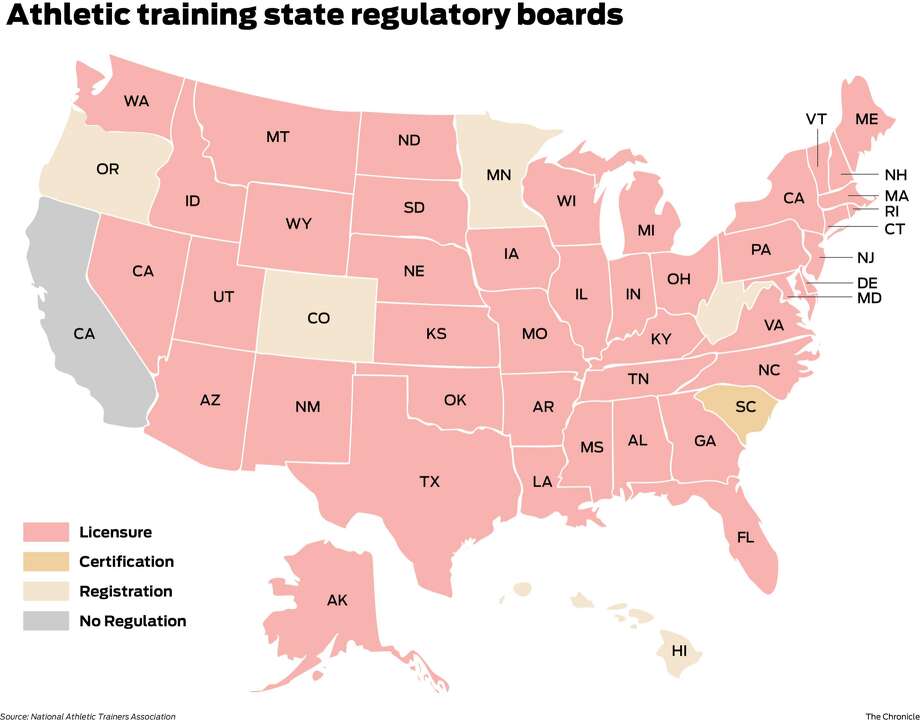

Missing from the equation, in many of those games, will be certified athletic trainers to watch over the proceedings, ready to address anything from common injuries to life-threatening situations. That’s because California is the only state that does not require its high school athletic trainers to be certified in any way. The state doesn’t even require schools to have trainers at games. So many do not.

It’s a shocking revelation, at a time when injury awareness and concern is at an all-time high — especially in football. We’re worried about the long-term effect of concussions, but we’re not even staffing high school football games with trained professionals? It’s an absurd situation that could be easily rectified.

According to a recent study published in the Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine and conducted by the University of Connecticut’s Korey Stringer Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to minimizing preventable death on the playing field, California ranks second to last in the nation — ahead of only Colorado — when it comes to implementing policies that help prevent the leading causes of sudden death in high school athletes. That dismal result is directly tied to the state’s lack of a coherent policy on trainers.

“California is the only state in the nation that does not regulate athletic trainers,” said Samantha Scarneo, director of sports safety for the Stringer Institute, named for a Minnesota Vikings lineman who died from heatstroke in 2001. “There’s been a lot of push to get licensure (legislation), but the governor keeps blocking it.”

Indeed, Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed bills in 2014 and 2015 that would have required athletic trainers to be educated and licensed. By explanation, he wrote that the bills would have required anyone using the title “athletic trainer” to go to college, and that would “impose unnecessary burdens on athletic trainers without sufficient evidence that they are really needed.”

Brown might face the issue again next year. There is a bill making its way through the Assembly — AB1510, sponsored by Assemblyman Matthew Dababneh, D-Encino (Los Angeles County) — that would require licenses for athletic trainers. If passed, it would be on the governor’s desk before next fall.

“I felt the need to take action in order for our state to properly protect our student athletes,” said Dababneh, in a statement to The Chronicle. “Athletic trainers are the expert on the sidelines, and the first people able to identify potential injuries. Parents trust these individuals to protect the health of their children but without proper education and training, signs of heatstroke or a concussion can be easily missed. By licensing athletic trainers, AB1510 will effectively protect the athletes by ensuring only qualified individuals can work as an athletic trainer.”

The bill faces opposition from the California Physical Therapy Association, which has held for years that there is no need for a layer of certification for athletic trainers. In a letter to Dababneh last spring, which addressed six concerns, the professional group said, “AB 1510 is highly flawed and addresses no pressing issues facing the State of California and its citizens. Instead this legislation seeks to benefit a single category of individuals.”

Digging a bit deeper, the physical therapists seem most concerned about the scope of the bill, fearing it would give athletic trainers too much leeway to practice medicine.

The bill “absolutely oversteps its bounds and would allow athletic trainers to practice in a way that they’re not trained,” said Chris Reed, a physical therapist and chair of the government affairs committee for the CPTA. “It would be great if we had a bill that would require a trainer on every sideline. This bill doesn’t do that.”

The athletic trainers counter by saying physical therapists are trying to protect their job territory. The argument between the two professional organizations has been going on for years, leading certification efforts down a political rabbit hole the Assembly will wrestle with again in the next session.

In the meantime, sports are being played and California remains the only state without a rational certification process.

“I’m very much for certification,” said Scott Heinrichson, 45, an accredited athletic trainer at St. Francis High School in Mountain View. “We’re dealing with kids on a daily basis. As a parent, you’d definitely want someone in there who is qualified to do that job, not just someone who just says they are qualified.”

We’ve all heard the horror stories. Just this season, a high school football player in Santa Rosa suffered a severe head injury that required brain surgery. During training camp over the summer, a young player in the Bronx collapsed and died, apparently from heat exhaustion. From 1982 to 2015, 735 high school athletes died during and after participating in sports, according to the University of North Carolina’s National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research. According to the Stringer Institute, the leading causes of this most tragic result are sudden cardiac arrest, traumatic head injuries, heatstroke and complications related to sickle-cell trait.

Any of those four medical conditions requires quick-thinking action from a trained professional. But too many California high school athletes are not getting that kind of treatment.

“Athletic trainers need to be licensed in California. The fact is that we deal with a variety of medical conditions on a daily basis, and yet there’s no regulation, there’s no mandate on qualifications,” said Mike Chisar, chair of the California Athletic Trainers Association’s governmental affairs committee. “We wouldn’t go to a physician that hasn’t gone to medical school. To see an athletic trainer to manage your concussion, when that trainer isn’t actually an athletic trainer, doesn’t make sense.”

In other states, athletic trainers need to be college educated, receiving training and degrees similar to other health care professionals, such as physical therapists, occupational therapists or physicians’ assistants.

“There are accredited programs,” said Chisar, an accredited trainer himself. “Every state utilizes the same accredited program. There is one national exam that validates whether you have the skills necessary to function as an athletic trainer. Every state uses it.”

Except California. And that’s why many high school athletes compete with no trained medical staff on hand.

“I’d say it’s about half,” said Heinrichson, when estimating how many Bay Area schools have qualified trainers. “If an emergency happens, are they prepared? You have concussions, and cardiac emergencies. Do you have someone who’s trained to work with that? You also need someone who’s qualified to make return-to-play decisions. Are they making the right decisions, in the best interest of the athlete?”

Of those schools that do have trainers, many aren’t qualified. According to a fact sheet attached to AB1510, “Fifteen universities in California, including seven CSUs, have nationally accredited athletic training education programs. Despite this fact, anyone can still act as an athletic trainer; approximately 30 percent of individuals calling themselves athletic trainers in high schools are not qualified.”

It’s not a pretty picture, but there are steps schools can take while waiting for possible legislative relief.

The Stringer Institute strongly recommends that every school have an emergency action plan, or EAP in trainer parlance, that answers some basic questions. Who should be calling 911? Who goes and gets the athletic director? Who directs (emergency personnel) to the field? What are the directions to the field? Is there a gate that needs to be unlocked?

“It’s a low-cost effort,” said the Stringer Institute’s Scarneo. “There are templates out there that schools can use. Mandating that schools should have a medically specific EAP for sports-related injuries is one area that California could score points, but more importantly save lives. That’s more important than licensure, in my opinion.”

Whether Sacramento listens to this advice, we’ll see. Brown’s office said it does not comment on pending legislation. Perhaps those nervous parents, sweating it out under the Friday night lights, can ask the governor and the Assembly to stop listening to the lobbyists on both sides of the legislative fight and do the right thing by the kids.

“Our message to parents is that if your school can afford to have a football team, they can afford to have an athletic trainer,” said Scarneo. “If they can’t afford an athletic trainer, they can’t afford to have athletics.”

Al Saracevic is sports editor of The San Francisco Chronicle. Email: asaracevic@sfchronicle.comTwitter: @alsaracevic

Tell us your stories

Has your son or daughter been injured while playing high school sports? Did you feel the medical care was sufficient, or not? Share your stories with The Chronicle, which plans to pursue the subject of high school athletic trainers in greater depth. Email Al Saracevic at asaracevic@sfchronicle.com.