When high school football practice begins for the 2015 season in Ohio on Saturday, coaches and players will be functioning under a new set of national guidelines addressing concussions, which was adopted and introduced by the Ohio High School Athletic Association on July 13.

In a memo to the OHSAA membership of more than 700 high schools, commissioner Dan Ross said the association “has joined dozens of states in adopting recommendations from the National Federation of State High School Associations’ Concussion Summit Task Force, which will reduce the risk in football for concussions and head impact exposure.

Ross has long stated that the top priority of the OHSAA is the safety of its athletes, and the new guidelines are designed to give football coaches some direction in the intended reduction, recognition, and treatment of head injuries in practices and games.

“With the support and leadership from the football coaches association, we have been out in front of concussion awareness and education, and these changes will now bring Ohio up to a place as a national leader in this area,” Ross stated in the memo. “Like many of our regulations, these guidelines are to be followed and monitored by member schools and coaches, but we are fortunate in Ohio that many coaches have already been following these safety measures.

“There will always be a risk for concussion, but football is safer now than it has ever been, and these guidelines will make it even safer.”

According to the OHSAA memo, the three principles that the guidelines reflect include exposure of an individual athlete to full contact in terms of frequency and duration, the cumulative effect of the exposure on an individual athlete, and recovery time for each athlete after contact.

The recommendations adopted include spring, summer and all off-season contact. Already the rule in Ohio, there is no contact permitted except during the season, and pads may not be worn at any time except during the season.

The new guidelines are aimed at preseason practice and practice during the season.

New to preseason practice, full contact will be limited during two-a-day practices.

When more than one practice takes place in a day, full contact is permitted only during one of the practices. Further, if full contact occurs during the second session of two-a-days, full contact will not be permitted during the first session the following day.

Once the season has begun, individual athletes are limited in full contact on consecutive days to 30 minutes in practice per day and to 60 minutes per practice week. An athlete can only be involved in full contact in a maximum of two practices in a seven-day span.

Contact with soft equipment such as bags, shields, sleds, etc., does not count toward full contact limitations.

“These regulations are being put into place for the safety of our student-athletes, and it is incumbent on coaches to monitor the contact in their practices,” Ross said. “Our coaches are educators and leaders. They want what’s best for kids, and these regulations are in line with these safety recommendations.

“These regulations will evolve and may become more restrictive as additional concussion research emerges.”

Adapting to the changes

The changes adopted by the OHSAA will not be viewed as drastic to most Ohio high school football programs, as many coaches had already become more vigilant to the potential for head injuries.

Head coaches at three of the Toledo area’s top football programs from recent seasons each said they have long been aware of the danger of concussions, and that the safety of their players is paramount.

Last season, coach Matt Kregel’s Perrysburg team finished 11-1 and was the top-ranked Division II team in Ohio. Greg Dempsey has coached Central Catholic to three state playoff championships in the past 10 years (2005, 2012, 2014). Whitmer’s Jerry Bell guided his 14-1 Panthers to a Division I state runner-up finish in 2012.

“I think we’ve always done a good job of controlling the hitting,” Kregel said. “We don’t have enough kids to two-platoon, so we have to monitor the hitting ourselves. I don’t think [the new OHSAA rules] will have a huge effect on us and how we coach things.

“We monitor ourselves. It’s a common-sense approach. We’ve always done it this way, and the good coaches in the area that I’ve talked to have said they’ve always done it this way.

“I don’t think this is going to have a huge effect on how guys coach high school football. At least for the guys who do the right thing and are concerned about the kids.”

Safety is first and foremost.

“I definitely think things have to be done to protect the kids that participate in football,” Dempsey said. “And, by doing so, you’re protecting the future of the sport.

“You definitely need to be better educated, and there needs to be some parameters set.

“I’d say 99 percent of the coaches are doing it right. But there’s some people who, for whatever reason, usually cause rules like this to be put into effect.”

Even though they already have the athletes’ safety in mind, there will be extra incentive for coaches to adhere tightly to the full-contact limitations.

“All it takes is one parent who’s unhappy with playing time to say ‘You’re hitting too much throughout the week,’ ” Bell said. “We’re going to monitor that throughout our practice plans and make sure we have it right.

“It’s for the safety of our kids. When you look at the way people are practicing nowadays, I think that we already err on the side of caution with concussions to begin with in making sure that the drills we’re doing are putting safety first, and teaching kids the fundamentals of the game.

“Over the years, we’ve learned how to do that without full contact. We want our kids healthy throughout the season, especially with the schedule we play. When I look at the new rules, it really doesn’t change much in how we practice. We’ve been doing this for years.”

Out with the old

Kregel, Dempsey, and Bell have each been around the game long enough to see the evolution of high school football practice from a more physically demanding and dangerous past to today’s more sensible training methods.

That includes greater awareness of head injuries.

“You can’t beat your kids up,” Kregel said. “There were years in the past when everybody was two tight ends and I-formations when that’s all you did was line up and bang. That’s not the case anymore. The guys who have sense will do it the right way.

“The guys who want to stretch the rules and do it the wrong way, I think that’s who this rule is for — to protect those kids. At the beginning of two-a-days, you’ll still have some kind of one-on-one, man-up kind of drills. You’ll do that for 10 minutes. Everybody bangs, and then you go to the next drill.

“But you do something where you’re not hitting full speed. We never just line up and knock the living crap out of each other for an hour and a half.

“I think that’s the direction football is going in. It’s not blood and guts and knocking the crap out of each other. You have to be smart about how you conduct business.”

Dempsey believes today’s high school football is a much safer version of the game.

“I feel better about kids playing football now than ever because of the awareness and the education and the protocol,” Dempsey said. “We’re much more aware and, when an event happens, the protocol for a kid’s return is much safer.

“If a concussion happens, it’s something we’ve got to watch. If two of them happen, it’s something we’ve really got to watch. Right now, I believe it’s as safe as it can be to play football.

“I think we know more about [recognizing concussions] now. It used to be macho to hide stuff as a player, and coaches used to make remarks about a kid having ‘his eggs scrambled’ and stuff like that. It’s much different now. You might even have some things now that are labeled as a concussion that really aren’t. But it’s better to err on the side of caution than it is to ignore it, which is what used to happen.”

Bell sees current high school coaches as much more enlightened regarding the dangers of the game.

“Overall, our coaching profession is very good at understanding the game and understanding the fundamentals, and how to teach the kids the fundamentals without putting them at risk,” Bell said. “The days of you running drills like ‘bull in the ring’ are long gone at the high school level. “With the research that they have done on concussions, and looking at long-term factors for kids with how it can impact them as adults, us being proactive on this is a step in the right direction.

“We can teach and do our jobs without having to put our kids at risk during the training sessions, and still have them function at a high level and be able to make a sound tackle and a good block with these new procedures in place.”

A watchful eye

According to information provided by the Mayo Clinic, signs and symptoms of a concussion might include headache or a feeling of pressure in the head, temporary loss of consciousness, confusion or feeling as if in a fog, amnesia surrounding the traumatic event, dizziness or ‘seeing stars,’ ringing in the ears, nausea, vomiting, slurred speech, delayed response to questions, appearing dazed, and fatigue.

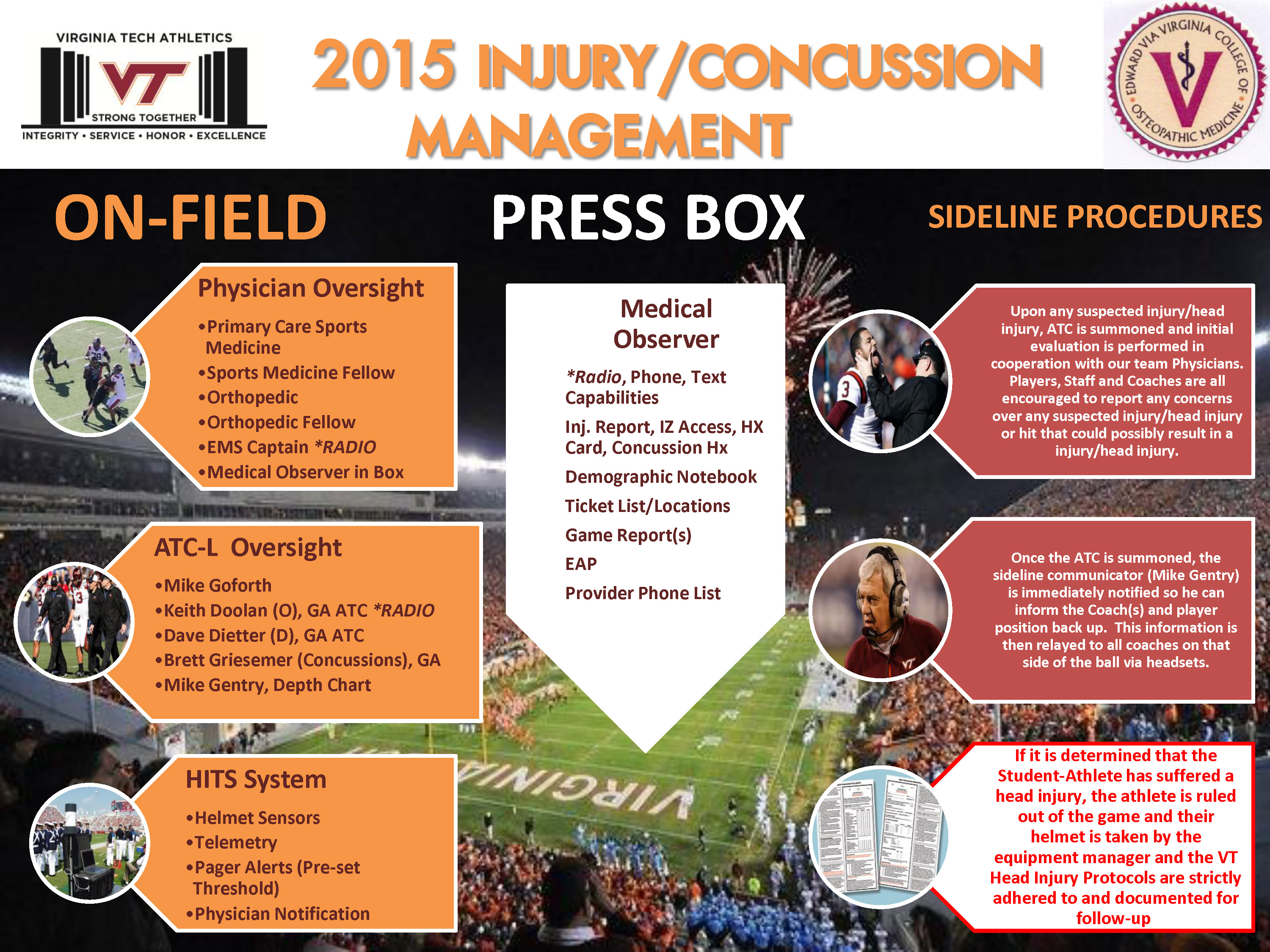

Coaches might not have the ability to diagnose such symptoms, but they have athletic trainers on hand at nearly all practices and every game, and many high school games are staffed by a team physician.

Perrysburg, Central, and Whitmer have a team doctor on hand at every game.

The coaches rely heavily on their athletic trainers to recognize potential concussions. Whitmer, like many area schools, utilizes athletic trainers provided through Mercy Sports Medicine, a division of Mercy Health.

Athletic trainers David Hamen and Aaron Sage work full-time with Panther athletics.

Hamen has been an athletic trainer since 2003 after earning his bachelor of science degree from Bowling Green State University. He has worked with Whitmer athletes since 2008.

As the 2015 football season approaches, Hamen has been busy utilizing one of the most important tools available to medical personnel in recognizing concussions.

He has been conducting what is called baseline testing for all of Whitmer’s fall season athletes who will be competing in contact sports. Nearly the entire football team has already been tested and placed in the accompanying computer system.

The trainers utilize Mercy Health’s ImPACT evaluation procedure to help diagnose concussions in athletes.

ImPACT, which stands for Immediate Post-concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing, utilizes neurocognitive baseline and post-injury testing to evaluate the athlete’s normal cognitive ability (baseline) versus his or her cognitive ability after a head trauma.

Mercy Health touts that this procedure — comparing baseline to post-injury function — as “the most scientifically validated computerized concussion evaluation system.”

In a nutshell, each individual athlete takes an online test to establish his or her normal “baseline” cognitive ability. When a possible head injury has occurred, athletes are retested to see if there has been a measurable dropoff in their cognitive performance.

“It’s a series of different tests,” Hamen said of ImPACT. “Some of it is a memorization of words, some of it is memorization of shapes or patterns. It gives us a baseline for where the kids are [in normal cognitive state].

“If we ever suspect there is a concussion, we’ll have the kid sit down and take the test again. It will give us a readout of where they were initially and where they are now. Depending on the score, it will give us a better idea if there’s a potential concussion there, and to seek further help. It’s a tool for us to help identify concussions, and to protect our kids.”

The high school football season, for most Ohio teams, begins Aug. 28.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE:

http://www.bcsn.tv/news_article/show/537483