The Mercedes-Benz had a navy blue exterior and tan exterior, Gary Vitti reminded himself as he walked out of an LAX terminal and toward a job he wasn’t even sure he wanted.

He was happy being the head athletic trainer at the University of Portland, not to mention an adjunct professor, and had already tasted a bit of the NBA via two years as an assistant trainer with the Utah Jazz.

When he saw the Mercedes, Vitti jumped into it and was immediately negative, complaining about the traffic in Los Angeles.

The driver was Lakers General Manager Jerry West, who took Vitti a few miles east for a three-hour interview at the Forum. Then Vitti met Coach Pat Riley, who was direct, even a little intimidating, when he said, “You’re not ‘scarred’ yet. I can mold you into being the best.”

e Mercedes-Benz had a navy blue exterior and tan exterior, Gary Vitti reminded himself as he walked out of an LAX terminal and toward a job he wasn’t even sure he wanted.

He was happy being the head athletic trainer at the University of Portland, not to mention an adjunct professor, and had already tasted a bit of the NBA via two years as an assistant trainer with the Utah Jazz.

When he saw the Mercedes, Vitti jumped into it and was immediately negative, complaining about the traffic in Los Angeles.

The driver was Lakers General Manager Jerry West, who took Vitti a few miles east for a three-hour interview at the Forum. Then Vitti met Coach Pat Riley, who was direct, even a little intimidating, when he said, “You’re not ‘scarred’ yet. I can mold you into being the best.”

Vitti was 30 at the time and immediately drawn to West and Riley. It wasn’t long before he became the Lakers’ trainer, a job he will leave after next season, his 32nd with the team.

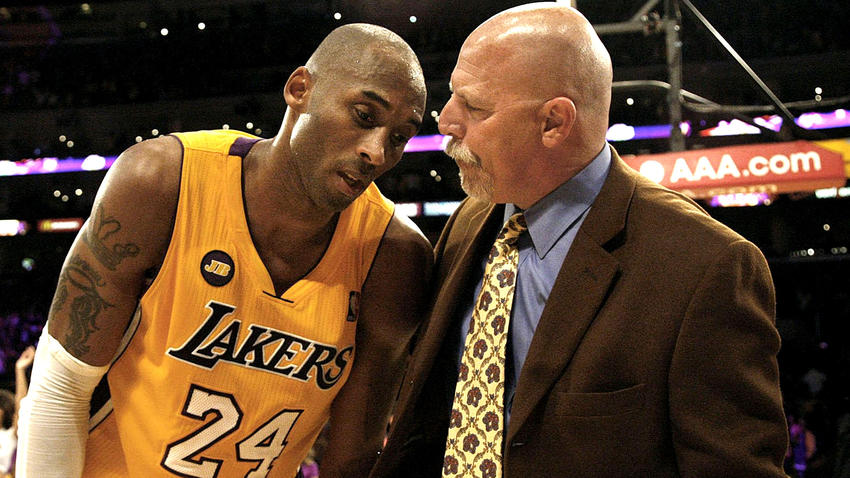

He’s been part of 12 trips to the NBA Finals, eight of them successful, and the players he took care of were as legendary as the franchise itself: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic Johnson, James Worthy, Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant among the many.

When Vitti started with the Lakers in 1984, he was only slightly older than most players. “Now I’m old enough to be their fathers and some, I guess, even their grandfathers,” he said.

Vitti, 61, remembered the good times and bad in an interview with The Times. He will remain with the team as a special consultant two more years after next season, but his traveling days will end, along with the team’s round-the-clock reliance on the NBA’s longest-tenured trainer.

He talks easily of the most memorable championships of his career, as well as Kobe Bryant’s future and another player’s injury last season that drove Vitti that much closer to retirement.

Many of Vitti’s anecdotes could serve as salves for Lakers fans at a time the franchise has struggled mightily, missing playoffs in consecutive seasons for the first time since the 1970s and bottoming out with a 21-61 record last season.

“From a basketball standpoint, the greatest championship would be 1985, the first time we beat Boston,” Vitti said as he slowly consumed an open-faced gyro at an upscale Manhattan Beach restaurant near his home. “We lost to the Celtics the year before and should have beat them. A lot of my interview with Riley was him talking about that. He said to me, ‘We need to win.’

“The first day of training camp in 1984, they started talking about beating the Celtics in the Finals in June 1985. Riley was our GPS. He knew where we were. He knew where we needed to go.

“We went on to beat Boston in six games. On their floor. It broke the curse of the Celtics.”

The only championship ring Vitti wears is the one from 1987, another victory against Boston, though his ring selection doesn’t have anything to do with basketball. It was the year his first daughter, Rachel, was born.

His second daughter, Emilia, was born in 1991 but the Lakers lost to Chicago in the NBA Finals that year.

Vitti’s ring choice actually riled a former Lakers player.

“Shaq gave me a lot of heat. He wanted me to wear one of the ones once in a while that I won with him,” Vitti said, alluding to championship runs in 2000, 2001 and 2002. “I probably should have but I never did. It’s not that I didn’t appreciate what those teams did and what they were. It was just a different mentality. It wasn’t who I was. I was forged as a Laker in the ’80s, not in the millennium.”

So much has happened the last few years, so little of it positive. Vitti even called it “a nightmare.” Few would disagree, the Lakers continually losing Bryant and Steve Nash to injury, along with a slew of games.

“When somebody gets hurt, I blame myself. That’s the Laker way — you’ve got a problem, you go in the bathroom, you look in the mirror, you start with that person,” Vitti said. “The one that really affected me and maybe even affected this decision [to retire] was Julius Randle. All of his doctors and his surgeon are saying that nothing was missed, but the guy goes out there and breaks his leg the first game [last season]. That one really bothered me.”

Vitti is often an emissary between players and management. He recently met up with Bryant, with whom he shares a longtime bond.

“He was asking about our young kids, and I said, ‘You cannot believe how quick and athletic Jordan Clarkson is. He looks fantastic,'” Vitti said. “I said I personally thought D’Angelo Russell is going to be a star. He makes hard things look easy when he has the ball in his hands.

“Then Kobe said to me, ‘Well, then who’s going to play [small forward]?’ I looked at him and I said, ‘You.’ And with absolute, 100% confidence, he said, ‘I can do that.'”

Can Bryant, soon to turn 37, really do it? His last three seasons were cut short by injury and he became a part-time player last season, sitting out eight of his last 16 games for “rest” before sustaining a torn rotator cuff in January. He is under contract for one more season at $25 million.

When Nash retired, that didn’t mean he couldn’t play in an NBA game. The problem was how much time did he need to get ready for the next game.” Vitti said. “He had lots of issues that prevented him from playing an NBA schedule.

“That’s going to be the big question with Kobe, and we’re just going to have to feel it out. It’s been a while since he’s played. We just need to see.”

Vitti has one more year to worry about bumps, bruises and otherwise the rest. Then they become someone else’s headache.

He will spend more time with his wife, Martha, and two daughters, no longer logging 320 days a year of work.

“It’s not like we’re in the salt mine, making big rocks into little rocks, but we have to be there mentally and emotionally in my position. You can’t check out at the end of the day,” Vitti said. “You go home, your phone’s on, you talk to players, you talk to management, coaches, agents, you talk to all of their families because if somebody’s kid gets sick, they don’t call the pediatrician, they call me.

“I don’t know why, but they do. I’ve had athletes bring people over to my house unannounced — they got hurt playing volleyball on the beach or basketball at [nearby] Live Oak Park.

Then he smiles.

“This job,” he says, “really was all-encompassing.”

ORIGINAL ARTICLE:

http://www.latimes.com/sports/lakers/la-sp-lakers-vitti-kobe-20150727-story.html