Article reposted from Tuscaloosa News

Author:

Every Alabama football player is required to have his ankles taped or braced for every practice or game. That means every player comes to see Jeff Allen and his staff before every practice and every game.

He’ll tape about 15 players a day before practice and more on game days. That’s about two hours of work every day. Some may consider it one of the more ponderous tasks of his profession. Allen doesn’t.

“It matters,” Allen said. “It’s not just a menial task. It matters.”

The way Allen – Alabama’s associate athletics director for sports medicine – sees it, about a quarter of the injuries he and the medical staff deal with are ankle injuries. That’s why every player is required to be taped, every day.

“If we don’t tape them and don’t do a good job of it, I guarantee you, our injuries are going to shoot up,” he said. “When I’m taping them, I’m like, ‘OK, I’m protecting this guy so that he can stay on the field.’ I’m not just throwing some tape on him. I’m doing it the right way, doing it the way that’s going to work biomechanically and physiologically so that we keep this guy on the field.”

So players begin putting their name on a list to be taped, and the process starts around noon. It goes until meetings at 2 o’clock on a normal practice day.

But there’s also more to it than biomechanics and ankle support. Those two hours every day are the time for Allen and the athletic trainers to build bonds with players.

“The guys that I tape every day, definitely it’s a great way to sit there and talk to them, just like a barber does when you sit there in a chair,” Allen said. “We certainly use that as an opportunity to build those relationships.”

Trust is key in the relationship between players and athletic trainers. The medical staff, by nature, will spend the most time with players who are injured. They’re the ones running on the field when a player stays down after a tackle.

The relationships have to start before then. Most athletes arrive at Alabama with no experience of working with a professional medical staff on a day-to-day basis. Allen and the medical staff have to build that trust before injuries strike. The alternative can be corrosive to a team’s culture.

“The main thing, and I’ve seen it happen where the athletic trainers, the players, and the coaches aren’t on the same page and there’s some controversy or lack of trust,” said Dr. Lyle Cain, an orthopedic surgeon with Andrews Sports Medicine. “What you see typically is unhappy players, number one. Because the players don’t trust the treatment that they’re getting. That’s a disaster. If the players feel like the athletic trainers are too much on the coaches’ side, or the doctors are too much on the coaches’ side or the team side, I think you totally lose trust in the system. They don’t get well as quickly. They don’t follow through on their plans for rehab, and it makes a difficult situation medically to deal with any kind of injury because the player really doesn’t trust what you’re telling them.”

Players may arrive with the idea that the medical staff are the ones who keep them from returning to the field. Allen, along with the team doctors and athletic trainers, are the ones who make that decision. But there’s also far more than that.

Allen and his staff are with players when they receive bad news. They’re the ones who translate medical diagnoses into a language that players and their families can understand. They have to communicate with the coaches and the strength and conditioning staff about what players can and cannot do.

Then they’re with players through their rehab. They communicate with doctors, specialists, families and players to keep them on track. Taping ankles is just the beginning. Allen and his team are known as one of the best in every area.

“I’ve been at Alabama almost 30 years and worked with some excellent athletic trainers, but Jeff’s overall package is just so unbelievable,” said Dr. Jimmy Robinson, Alabama’s team physician.

It starts with those relationships. It’s built over time, on the training table before practice or in the rehab room. Robinson said the medical staff gathers before games to say a prayer that there won’t be any injuries.

“He loves on them, to be honest with you,” Robinson said. “He gives them a hug and puts his arm around them and talks to them.”

The medical team is more than just Allen, and more than just the athletic trainers. Robinson and the team physicians play a big role. Andrews Sports Medicine is one of the premier practices of its type anywhere, and it happens to be just down the road.

But Allen is the one who oversees it all as the head athletic trainer for the football team.

“I’ve told my other doctors that I work with and the other people around that I think there are several people important to the University of Alabama program,” Cain said. “Obviously Coach (Nick) Saban is at the top of the list. But I think Jeff Allen is probably in the top two or three. There is no coach, administrator, doctor or anybody else in the program that’s as important in terms of what happens through the season, what happens in the offseason, what happens with the players from a perception and happiness standpoint as Jeff Allen.”

Allen and the medical staff have been especially vital to Alabama this season. The Crimson Tide watched four of its top linebackers go down to injury in the season opener against Florida State. Outside linebacker Anfernee Jennings had surgery for an ankle injury and played three weeks later against Vanderbilt. Inside linebacker Rashaan Evans made a return from a groin injury in that game, too.

Outside linebackers Christian Miller (biceps) and Terrell Lewis (elbow) were also hurt in the opener and expected to miss the rest of the season. Inside linebacker Mack Wilson (foot) was injured in the LSU game, but missed just one game and played in the Iron Bowl.

“I don’t know that we’ve had more (injuries this season),” Allen said. “We’ve had more to one position. That’s the problem. Usually they’re spread out among the whole team and you can kind of absorb them. When you have that many to one position, that’s really hard to manage.”

Even when Miller and Lewis were declared out for the season, Allen and his team went to work and tried to find new ways to help players return to the field sooner.

“We modify different braces or create braces or make braces that prevent that structure from being reinjured. Like the elbow braces that Christian Miller and Terrell Lewis are wearing,” Robinson said. “Mack has a special orthotic in his shoe that’s custom-made for him that protects that bone from having too much stress on it. Things like that are invaluable.”

If Alabama can win a championship with those linebackers back on the field, it won’t be the first time Allen and the medical staff have helped put the Crimson Tide over the top.

They also had a key role in the 2015 championship. Senior running back Kenyan Drake broke his arm against Mississippi State on Nov. 14 of that year.

Before Drake had even left the field, he and Allen were talking about his timetable to return. Drake declared that night that he’d be back for the SEC championship game – and he was.

“I don’t think there’s any question that between him and Dr. Cain, they’re able to get these athletes back faster but also safer than most programs,” Robinson said.

Cain operated on Drake as soon as possible. Allen had a carbon fiber brace 3D-printed with the help of Alabama’s engineering department for Drake to wear. He had a machine that he wore on his arm while sleeping to help his treatment. He was in the training room to rehab whenever he could be.

Drake caught a pass on Alabama’s first play from scrimmage in the SEC title game. He swung to the left side, moving the ball into his healthy arm. He used his right arm – broken less than a month before – to stiff-arm a defender. He didn’t even realize it until he was back on the sideline and Allen asked him how it felt.

“They did all they could to help me get back, working with the engineering program, getting a carbon fiber copy of my arm and putting the whole cast around it,” Drake said. “It was a real team effort and I appreciate everything they did for me.”

The real dividend came a month later in Phoenix. Drake returned a kickoff 95 yards for a touchdown against Clemson in the fourth quarter of the national championship game.

“It would have been really easy with Kenyan to put him in a cast and say, ‘Hey, good luck to you. You’ll get better in 8-10 weeks and you can start trying to come back.’ That cast probably would have cost $15,” Allen said. “Dr. Cain took him the next day and did a very aggressive procedure, put a plate over the fractured forearm, we put him on a bone stimulator, started doing aggressive rehab. Stuff that’s incredibly expensive, but I think the return on the investment was pretty good.

“If we don’t have him in that national championship game, I don’t know if we win it. I really don’t. I don’t know if we win the game.”

Allen has a mural in his office of Drake diving across the goal line on that play. He’s holding the ball in his right arm: the arm that was broken.

That comeback was made possible not just by the aggressive treatment, dedicated rehab and top-of-the-line medical care. It also happened thanks to the relationship Drake had with the athletic training staff.

He’d dealt with a major injury the year before when he broke an ankle and was out for the season. Allen and the medical team helped him come back from that. He knew he could trust them.

“Obviously, when you’re hurt, it’s a way deeper relationship than just getting your ankles taped,” Drake said. “It wasn’t strange when I had to go through the rehab because you’re already familiar.”

As much as anything else, that’s what sets Alabama’s medical staff apart.

“I think in a lot of places, he would not have been on the field,” Cain said. “But I think he was (able to return) primarily because of his confidence in the athletic training staff and the rehab and the process that he had already experienced. His mentality was totally different than it would be at most places.”

After the game, there was a moment when Drake, Allen and Cain embraced. Allen said it was the “most special moment” he’s experienced in college athletics. The relationship remains, even after Drake’s college career ended that night.

“When I go to campus, one of the first stops I make is the training room,” Drake said.

He’s not the only one. Washington Redskins defensive end Jonathan Allen stopped by earlier this season after an injury likely ended his rookie year. The offseason sees “a flood” of former players coming in and out: Eddie Lacy, Eddie Jackson, AJ McCarron, Dre Kirkpatrick, Dont’a Hightower and C.J. Mosley were just a few who came through.

Cain said that many former Alabama players who have gone on to the NFL will call Allen for advice when they’re injured. They trust that he’ll have their best interest in mind.

“They want to keep players on the field,” Drake said. “That’s what they do. That’s what they do best. I don’t think anybody else in college football or anybody in the world does a better job than Alabama.”

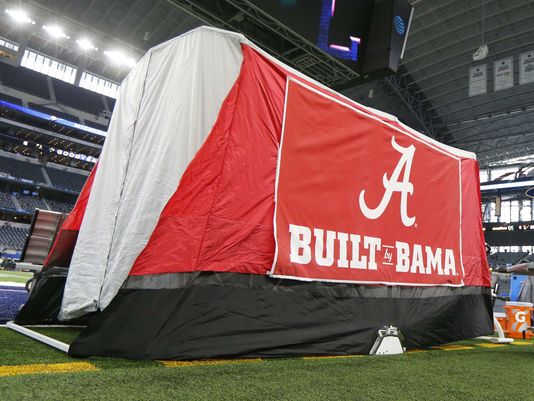

Jeff Allen’s concern for players is also on display with the sideline medical tent the Crimson Tide has used since the 2015 season. Allen developed the tent with a pair of Alabama engineering students, and the concept spread around the country. The tent sells for $5,000.

The tent gives the athletic trainers and doctors a modicum of privacy on the sideline to examine players. If there’s bad news, the players can hear about it without the world knowing.

“We’ve had games with a camera right over top of us,” Allen said. “It’s crazy. It’s very hard to get a good evaluation. It’s obviously very taxing on the kid. We did it with the idea of privacy in mind and knowing it would help from a privacy standpoint. What I didn’t really fully appreciate until now, is how much more relaxed we all are in there. Thus, the evaluation is better. I feel like we’re getting a much better medical evaluation simply because we take away all the distractions that are so prominent on a sideline.”

It was a simple fix to a problem that had existed for years for men and women in Allen’s position. He just happened to be the first one to think of it.

That’s what Allen has always been after: an innovative solution. It puts the players first. It improves medical care.

Earlier this year, Allen was walking into Alabama’s practice when someone asked how sales of his new invention were doing.

“Still taping ankles,” he said, smiling.

Then he walked into practice.

Reach Ben Jones at ben@tidesports.com or 205-722-0196.