On its opening day, I watched the movie, “Concussion,” and thought as I walked out of the theater that it could change the game of football and the way concussions are viewed by the public. I thought it might also create a more conservative approach in management by medical professionals.

“Concussion” depicts the story of a neuropathologist, Dr. Bennet Omalu, played by Will Smith, and his struggle to warn the National Football League of a brain condition that he discovered in autopsies of former NFL players — Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Omalu made his discovery of CTE in 2002 during his autopsy of Mike Webster, the Pittsburgh Steelers’ Hall-of-Fame center who’d fallen on hard times in his retirement. Omalu later discovered CTE in other former NFL players who displayed behaviors usually attributed to older patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Omalu’s discovery of CTE in former NFL players not only went unheeded by the league and its Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI) committee, but the NFL went on a full blitz to deny the existence of CTE and to discredit Omalu and his findings. As Omalu’s mentor and boss, Dr. Cyril Wecht (played by Albert Brooks), said: “You’re going to war with a corporation that owns a day of the week. The same day of the week the church used to own.”

Based on my practical experience as a certified athletic trainer, I can see the relevance of this movie regarding brain injuries to athletes and future changes in both the game of football and how the concussed athlete’s care is managed.

The acting in “Concussion” is excellent and captured the reality of the concussion debate now raging in athletics. In addition to Smith, the cast includes Alec Baldwin, playing the role of Dr. Julian Bailes who joins Omalu to raise awareness of CTE and the long-term consequences of concussions on athletes.

(I am privileged to know Dr. Bailes, and though in real life he is more soft-spoken than Baldwin is in the movie, Baldwin does capture the intensity and passion that Bailes exhibits when he speaks of concussions and their consequences.)

Though he is only in one full scene and in the background of another, Arliss Howard portrays a riveting character as Dr. Joseph Maroon, the Steelers’ team neurosurgeon, who, in a key scene, portrays the anxiety felt by the NFL’s MTBI committee and its attempts to discredit the findings of CTE in former NFL players. The issue is not with science; rather, it’s with the impact that this revelation may have on the multi-billion-dollar business of professional football.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that there are at least 300,000 sports-related concussions suffered annually in the United States. “Concussion” highlights the severity of concussions on players and those attempts to keep quiet the potential long-term consequences of concussions while playing football. As a result, “Concussion” should further the ongoing discussion of concussions and also of their management and potential long-term consequences not just on football players, but for all athletes who experience concussions.

As a certified athletic trainer with nearly 40 years of experience in caring for thousands of injured athletes, I assessed and helped manage the recovery of hundreds of concussions suffered by student-athletes for 35 years as a staff member of the Syracuse University Sports Medicine Department.

Additionally, I was a participant in the 2010 NCAA Concussion Management Summit that established guidelines for concussion management in intercollegiate athletics. Moreover, as National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) liaison to the NCAA Football Rules Committee for two terms, I wrote the language for the helmet-contact penalty and defenseless-opponent penalty you now see being called in intercollegiate football. (As NATA liaison, I supported the game disqualification of football players who “target” their opponent with their helmet. I also wrote a passage in the 2008 NCAA Football Rules Book on concussion awareness.)

“Concussion” focuses on CTE and concussions, which are related but separate.

A concussion is a complex physiological process affecting the brain as a result of a hit to the head or the sudden stopping of the rapidly moving head, resulting in impairment of function that usually resolves spontaneously over time. Importantly, one does not have to be knocked unconscious to have a concussion. A concussion is a functional disturbance of the brain, while CTE is a neurodegenerative disease associated with Tau protein, which is normally found in the brain and acts as a lubricant in its function, collecting pathologically in different regions of the brain. It is the Tau protein abnormally collecting in the brain of former NFL players that Smith, playing Omalu, discovers in the movie.

CTE is a result of repeated mild traumatic brain injury as a result of chronic trauma to the head in some people. This chronic trauma is in the form of “subconcussive” blows to the head, whereby the blows to the head may or may not cause athlete-reported concussion symptoms, but nevertheless cause trauma to the brain, with repetitive blows to the head. While CTE is associated with older individuals, former college football players who committed suicide in their 20s were also found to have CTE on autopsy.

Not every athlete or person who is subjected to subconcussive hits to his or her head acquires CTE. Keep in mind that though the focus of concussions and CTE is on football players, any athlete, male or female, playing in sports where contact is present can suffer a concussion.

In “Concussion,” no player was disqualified for a concussion or concussion-like symptoms. Competitive athletics end for every athlete. We must protect the athletes from themselves — that is, from making decisions to continue playing with a potentially disabling condition they later would regret.

Some physicians in “Concussion” expressed regret that they didn’t disqualify a player with repeated concussions after seeing the after affects and Omalu’s CTE findings. My experience at SU was the opposite. I am satisfied that the team physicians did the ethical thing and medically disqualified student-athletes from participation as a result of repeated concussions.

Some of the medically disqualified student-athletes later told me they didn’t like the decisions, or the team physician(s) for that matter, at the time. But all are thankful now because they said — though cognizant that they were affected by their concussions — they were afraid of being stigmatized by their disqualification and of losing their identity as athletes, and would have continued to put themselves at risk had we not stopped them.

But back to “Concussion,” the movie …

Gugu Mbatha-Raw, as Prema Mutiso-Omalu, plays the supportive girlfriend and later spouse of Smith throughout the movie. Her line, spoken to Smith — “If you know, you must speak (the truth of CTE)” — is her best one and captures the essence of the film’s goal: To warn players, medical staffs, the NFL and those millions of fans that concussions, and every-day hits to the head while playing football, are serious matters that could lead to a life-altering condition such as CTE.

There is some Hollywood license taken in “Concussion,” which varied from the book by the same title upon which it is based. But that is the usual case in movies. However, even with these departures from the book, one of the film’s final scenes is both haunting and poignant … and reminds the audience that football players may be today’s version of gladiators, but they are people first.

I give “Concussion” three stars out of four for portraying the reality of concussions and CTE, as well as furthering the conversation of protecting athletes’ long-term well-being. The movie “speaks the truth” to the consequences of concussions on athletes. I believe it will not only change the game of football, but also the way in which concussed athletes are treated in the future.

Education regarding the signs and symptoms of concussion and potential long-term consequences (i.e., Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), among other issues) need to be fully explained to both athletes and parents of minor-aged children engaged in sports, especially contact sports.

Some athletes try to “tough out” their concussions by not reporting them for fear of being removed from participation, or upsetting their coach, teammate or parents.

Unfortunately, there are still some coaches who continue to stigmatize by proclaiming that concussions are simply “part of the game” and that athletes who succumb to them are “soft.” These coaches encourage athletes to hide their injuries, or soldier through them, in order to keep the players on the field. Or because that is what these coaches did as players in more unenlightened times.

This unethical practice must come to an end immediately.

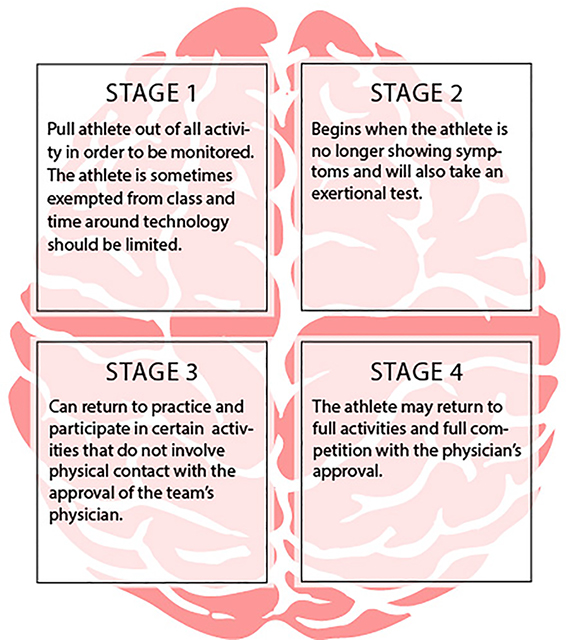

Return-to-play protocols following concussions are where most mismanagement occurs. It is important that the athlete be free from all concussion symptoms, that any neuropsychological tests are at baseline levels, and that the athlete is fully engaged in the classroom before the return-to-play protocol is implemented.

Some concussions are mismanaged because the preceding elements were not in place, or were not properly monitored and documented by medical professionals trained in concussion management, prior to returning the athlete to full participation.

Athlete medical disqualification based on concussion history remains a controversial topic. However, team physicians and athletic trainers, as well as coaches and administrators, have an ethical duty to care for and protect all athletes’ long-term well-beings. The question for team physicians is this: What is the magical number of concussions that an athlete can sustain before he or she should retire from contact sports?

There is literature to suggest that three concussions increase the vulnerability of more concussions with less force, placing athletes at risk for potential long-term consequences such as post-concussive syndrome and CTE. In collaboration with team physicians, we included the stipulation in SU’s Concussion Management Plan that the threshold of three diagnosed, time-loss concussions be consideration for possible medical disqualification.

During my tenure at Syracuse, there were student-athletes in other sports besides football who were medically disqualified because of their concussion histories. This is unpopular with athletes, sometimes with their parents, and too often with coaches. No matter how unpopular the decision is to medically disqualify an athlete, the team physician, in consideration of all facts and recommendations from credentialed medical professionals, has the legal authority to make the final determination regarding an athlete’s medical clearance.

Athletes may also “doctor shop” for someone, anyone, to clear them to resume participation despite a concussion history. Again, a good deal of medical disqualification is based on the vulnerability of sustaining further concussions with milder blows to the head after receiving the third concussion, especially if the concussions occurred at a younger age.

Concussion mismanagement is a liability issue for secondary schools, universities and insurance companies. Litigation on behalf of athletes who have had their concussions mismanaged is growing and will become more prominent in the future. As mentioned in the closing of “Concussion,” the movie I reviewed in the first part of this two-part series, there has been a class-action lawsuit by former NFL players against the NFL as a result of mismanaging their concussions during their times as NFL players.

Regarding the treatment of concussions, particularly for the “concussion” clinics that are growing in number, the goal in care should not be to get the athlete back to participation following a concussion as quickly as possible to satisfy a desire by the athlete — or his or her families … or his or her coaches — to get back to sports. Instead, the goal should be to treat the athlete as a patient who has a medical condition that needs specific care to return to a normally functioning life before returning, if ever, to competitive athletics.

The certified athletic trainer is a credentialed professional who is also a state-regulated medical professional in 48 states and has been educated and trained in concussion evaluation and management. The certified athletic trainer is usually the medical professional implementing the return-to-play protocol as well as making the initial concussion assessment and referral. However, there is a growing concern within the athletic training profession regarding interference on the part of some coaches — many with high salaries, nearly all under intense pressure to win — who have an interest in their players’ continuing to inappropriately participate with injuries, particularly concussions.

Though I never personally experienced such pressure at Syracuse University, I am aware of other athletic trainers who have lost their jobs or have been removed from football coverage by coaches or administrators (i.e., non-credentialed medical people) made unhappy by decisions/suggestions to remove injured athletes from competition. Often, these folks lobbied for “their own guys” caring for the athletes, a movement resulting in major conflicts of interest.

Unfortunately, athletic and university administrators empower certain coaches to control all aspects of their programs, sometimes sports medicine included. This is a bad precedent for the potential well-being of athletes and can reflect poorly on institutions. Such was the case this past summer when the University of Illinois fired its head football coach, Tim Beckham, after it was determined that he’d attempted to unduly influence medical decisions and care.

One suggestion to create the autonomy necessary to make medical decisions based on the long-term well-being of athletes is to have the university sports medicine personnel report to a department outside of athletics. The responsibilities of athletic trainers and team physicians are to ensure the health and welfare of the student-athletes, not team success. Thus, they should be judged on their quality of care and not by the traditional standards of number of active participants, or how fast they get athletes back from injuries, including concussions.

There are some university sports medicine departments that report to the university health service or medical school. However, not all schools have such relationships.

In any of those cases, a sports medicine department could report to a university panel — an athletic medical review board comprised of personnel who have experience in ensuring compliance with laws, national standards and best practices, and are not subject to conflicts of interest with unpopular-yet-necessary medical decisions that protect student-athletes’ long-term well-being.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Editor’s Note: Much like the movie, “The Express,” there have been accusations leveled by critics who insist that the makers of “Concussion” took periodic liberties with the truth in their film dealing with concussions and CTE in the NFL.

The following is a brief email sent to Timothy Neal from Dr. Joseph Maroon, who was mentioned in Neal’s piece (Part I of this two-part presentation) that was posted in this space at 10 a.m. on Thursday, Dec. 31:

Tim:

Well-written editorial. However, the scene depicted in the movie never occurred and at no time did I “discredit” Omalu or his work. I have spent, like Julian Bailes, my whole career trying to protect athletes — Baseline Impact testing has now been done on 10 million athletes. And it was I who encouraged the NFL to look further into CTE. Regardless, keep up your great work and best wishes for the New Year.

— Joe

Joseph C. Maroon, MD

Professor and Vice Chairman

Department of Neurosurgery

Heindl Scholar in Neuroscience

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Team Neurosurgeon, The Pittsburgh Steelers

www.josephmaroon.com

ORIGINAL ARTICLES(2):

http://www.syracuse.com/poliquin/index.ssf/2015/12/concussion_the_movie_may_change_the_way_football_is_played_and_viewed_part_i_of.html

http://www.syracuse.com/poliquin/index.ssf/2016/01/coaches_must_give_way_to_medical_professionals_in_the_area_of_concussions_part_i.html